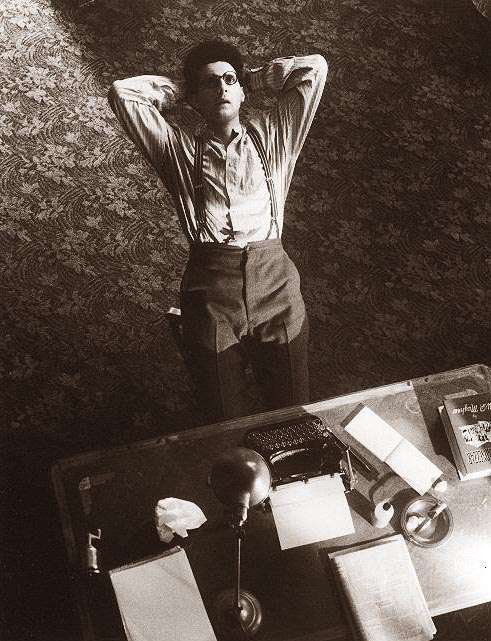

Writers are anxious people. Or maybe they're not, generally. I don't know enough of them to have a representative sample.

But I am.

I worry and fret over concepts, over how a thing works or does not work. There'll be a great rush of creative energy, and then, the final product before me, I'll start picking and scratching at it. What if this doesn't work? What if this is useless and pointless? Have I erred? Am I a fool and an idiot, so lost in my own dreamings that the universe itself can't help snicker at me? Am I getting this all wrong, on some fundamental level?

So. Here are my anxieties about When The English Fall, which will be my first published novel, categorized for your schadenfreude:

But I am.

I worry and fret over concepts, over how a thing works or does not work. There'll be a great rush of creative energy, and then, the final product before me, I'll start picking and scratching at it. What if this doesn't work? What if this is useless and pointless? Have I erred? Am I a fool and an idiot, so lost in my own dreamings that the universe itself can't help snicker at me? Am I getting this all wrong, on some fundamental level?

So. Here are my anxieties about When The English Fall, which will be my first published novel, categorized for your schadenfreude:

1) The science of solar storms. The key, transitional, apocalyptic moment of the novel is what appears to be a solar storm, one modeled after the Carrington Event of the late 1850s. The Carrington Event...the largest observed solar storm of the modern era...was an impressive thing. Telegraph systems were blown out. People touching metal farm equipment were given electric shocks. The resultant aurora were so bright that people came outside, thinking the sun had risen. It was a big deal, and would be a major concern in our technological society. That sort of catastrophic coronal mass ejection would completely devastate our vulnerable electronic systems. Our power grid and the internet would be significantly compromised. It'd be a big deal, one that we're unprepared for as a global culture.

But would it have the extreme effects outlined in the book, which are largely modeled after the localized electromagnetic pulse effects of a nuclear blast? That's not clear. Aircraft, vehicles, and grounded systems might not be impacted as substantially. Energies could have to be an order of magnitude higher to confidently project those effects. Could a Super-Carrington occur? Maybe. But my inner Bill Nye has lingering questions about whether the G-type main-sequence yellow dwarf our planet orbits is capable of that kind of violence.

But would it have the extreme effects outlined in the book, which are largely modeled after the localized electromagnetic pulse effects of a nuclear blast? That's not clear. Aircraft, vehicles, and grounded systems might not be impacted as substantially. Energies could have to be an order of magnitude higher to confidently project those effects. Could a Super-Carrington occur? Maybe. But my inner Bill Nye has lingering questions about whether the G-type main-sequence yellow dwarf our planet orbits is capable of that kind of violence.

What science does show us is that such an event...as described, precisely...is entirely possible. It might not come from our sun, but from extrasolar activity. A nearby supernova or a burst of energy from the collision of two neutron stars in our galactic neighborhood would have catastrophic impacts that would equal or exceed what's described in the book.

We and our tender little jewel of a world are very, very small and breakable in the vastness of Creation. That said, I'm sure some INTJ out there will roll their eyes and write a long and meticulously scathing review on Goodreads.

We and our tender little jewel of a world are very, very small and breakable in the vastness of Creation. That said, I'm sure some INTJ out there will roll their eyes and write a long and meticulously scathing review on Goodreads.

2) Lancaster County, PA. I've taken liberties with the geography, in ways that anyone who lives in and around Lancaster would recognize. I've been to the area, and gotten the lay of the land, more or less. I've walked the town, stood in fields, puttered down roads on my motorcycle. I've pored over GoogleMaps to map out movements and sightlines.

But I do not know the area in the way that you instinctively know a place you've lived. It's "sort-of-Lancaster." And sort of not, with the difference being driven by the needs of the narrative.

On the one hand, my perfectionist self is slightly embarrassed by this. Surely, surely, it could have been more perfect. On the other...well...it's creative license. And I don't want this to seem like I'm calling out one particular Amish community, because it's not.

But I do not know the area in the way that you instinctively know a place you've lived. It's "sort-of-Lancaster." And sort of not, with the difference being driven by the needs of the narrative.

On the one hand, my perfectionist self is slightly embarrassed by this. Surely, surely, it could have been more perfect. On the other...well...it's creative license. And I don't want this to seem like I'm calling out one particular Amish community, because it's not.

Which gets to area of fretting number three:

3) Amish Culture and Folkways. My experience of the Amish is at a point of academic remove. Meaning, I've read up on them, and not just on the interwebs or wiki. I've studied the best academic ethnographies of their communities, both on my own and as part of a formal academic course of study. I've read literature written by Amish voices, listening carefully to tone and perspective. I've done everything in my power to accurately represent the dynamics of that life. I have an informed take.

But I've not lived it. As a writer and a Presbyterian pastor and a doctoral student and a stay-at-home Dad shuttling kids to and from swimming and drums and afterschool activities, I didn't have the time or the bandwidth to go and live with the Amish.

"Hey, honey, can you get them to rehearsal this evening? I'm going to go live amongst the Amish for eighteen months." One does not say that to any wife one wants not to become an ex-wife.

I also wasn't sure if it would have been a good thing.

But I've not lived it. As a writer and a Presbyterian pastor and a doctoral student and a stay-at-home Dad shuttling kids to and from swimming and drums and afterschool activities, I didn't have the time or the bandwidth to go and live with the Amish.

"Hey, honey, can you get them to rehearsal this evening? I'm going to go live amongst the Amish for eighteen months." One does not say that to any wife one wants not to become an ex-wife.

I also wasn't sure if it would have been a good thing.

First, because the Amish honestly don't like that attention. They don't want to be viewed as a curiosity, to be observed and analyzed and photographed, tagged and released like some peculiar specimen. It can feel, for them, a bit invasive. Their culture lacks our individualistic love of attention, our net-era hunger for fame. Our peculiar obsession with their chosen path can also feel like an invitation to that kind of pride, which is anathema to their way of being.

And second, I'm not sure if that precision would help, given the complex and branching variance in Amish life. There is no one definitive way of being Amish, no single Ordnung. There are, instead, countless fragmentations, each arising from a point of decision in which one community took one path, and a group of dissenters took another.

What I've presented is an amalgam, a community that blends features of various different takes on that fascinating, unique form of life. The core principles are there, and they're as cleanly presented as I can make them. But it isn't perfect.

It'll read wrong, to someone, somewhere.

What I've presented is an amalgam, a community that blends features of various different takes on that fascinating, unique form of life. The core principles are there, and they're as cleanly presented as I can make them. But it isn't perfect.

It'll read wrong, to someone, somewhere.

4) Jacob's Voice. Having read Amish writings, and with a sense of the journaling in an agrarian context, I took my initial swing at writing what was then called The English Fall in the summer of 2012. It's a first person narrative, and the "voice" in such a telling matters.

About eight thousand words in, I ground to a halt. My first Jacob just couldn't tell the story. It's not that the story wasn't there. It's that he was so simple, so laconic, and so earnest that he wasn't...how to put this...interesting. He didn't play with words, but instead used them simply as tools to record events.

About eight thousand words in, I ground to a halt. My first Jacob just couldn't tell the story. It's not that the story wasn't there. It's that he was so simple, so laconic, and so earnest that he wasn't...how to put this...interesting. He didn't play with words, but instead used them simply as tools to record events.

He was too Amish, too plain. He was too much like a 19th century farming ancestor, whose diaries my family has retained. Every day, my great-great-grandfather wrote entries about livestock, just a sentence or two, marking the relevant memories of the day. When his five year old daughter fell ill with what was likely influenza, he described her decline with the same terseness. A word here. A short sentence there about doctors.

On the day she died, he wrote: "N passed today. What a patient little sufferer." That's it. All he had to say, two matter of fact sentences, about the death of his child. Authentic as it may be, it's hard to build a 54,000 word manuscript on such a voice.

I stepped back, gave it a year, and when I returned, Jacob was different. More...English...in his use of language. More introspective. Perhaps, again, he might not sound right in the ears of those souls who live in Amish communities. But the needs of the telling dictated the dynamics of his voice.

5) The Unknown Unknown. There may be stuff I just don't know I'm getting wrong. There very well could be. Somewhere in there, a fatal flaw, a critical error of continuity and narrative logic that through some terrible twist of fate my excellent editors just...missed. This is wildly unlikely and faintly insane. But this year, wildly unlikely and faintly insane things have happened.

And so, I fret. Guess that comes with the territory.

On the day she died, he wrote: "N passed today. What a patient little sufferer." That's it. All he had to say, two matter of fact sentences, about the death of his child. Authentic as it may be, it's hard to build a 54,000 word manuscript on such a voice.

I stepped back, gave it a year, and when I returned, Jacob was different. More...English...in his use of language. More introspective. Perhaps, again, he might not sound right in the ears of those souls who live in Amish communities. But the needs of the telling dictated the dynamics of his voice.

5) The Unknown Unknown. There may be stuff I just don't know I'm getting wrong. There very well could be. Somewhere in there, a fatal flaw, a critical error of continuity and narrative logic that through some terrible twist of fate my excellent editors just...missed. This is wildly unlikely and faintly insane. But this year, wildly unlikely and faintly insane things have happened.

And so, I fret. Guess that comes with the territory.