The Constitution of the United States is an interesting document.

It's not simply that it's the foundation of our system of government, the still-fledgling two-century-and-change republic that we inhabit.

It's that it's really a very functional document. This is not a place one looks for soaring prose about liberty and freedom, though that's in there here and there. Most of the Constitution is as exciting as reading organizational bylaws, because that's what it is. It establishes the structure and framework of our democratic processes.

That, once you've stopped humming the preamble, is exactly what it does. Nothing more, nothing less. It's a rubber-meets-the-road document, one that gets the job done without muss or fuss and hoo-hah, kind of like our just-the-facts-ma'am flag. That's what I like about it, because America at her best is all about just getting it done.

But the simple goodness of that document stands in tension with a peculiar worship that seems to have taken hold among a certain kind of "patriot." The Constitution becomes both Holy and Magic, although it was written intentionally to be neither. It is, as it so pointedly tells us, a document created by human beings for human purposes. It starts out "We The People" for a reason.

That strange idolatry has resulted in an even deeper irony, a cognitive dissonance so deep that it can't be described as anything other than pathological.

The same folks who have turned the Constitution into a totemic fetish distrust anyone who has actually participated in the government the Constitution creates. It is document that is the rule of our national life, that creates the process by which our system of governance works. Meaning, it is the foundation of our political system.

But to participate in our Constitutional system of governance makes you inherently suspect. You're just one of those Washington fat cats, an insider, just another purveyor of politics as usual. The moment of that transition comes the instant you're elected, apparently, which is why having actual experience in Constitutional governance is viewed by so many as a liability.

For those who fetishize the Constitution, it's better to be a talking head. Or, given this political season, an author or celebrity huckster or failed business leader. That view makes souls vulnerable to hearing the voices of those who manipulate and attack the system, the unelectable radical ideologues who'd rather spin out their stories of a bright, cold, faraway imaginary "Constitution" than engage with the reality the authors of the Constitution ordained and established.

Those who treat the Constitution like an idol are, in many ways, the same as the fundamentalists who worship the authority of the Bible. By treating it as something other than a rule for living well together, it makes it far easier to ignore the reality of it, and to subvert the way of life it seeks to shape.

Wednesday, September 30, 2015

Thursday, September 24, 2015

Pope Francis and Qualitative Leadership

Having just completed my doctoral work on healthy small churches, I'll occasionally be asked: so, um, what makes a small church healthy?

The answer people want to hear is quantitative. They want numbers and data. They want a specific program and pattern that is "replicable" and "scalable." When you think about church like a corporation or institution, that's just how you think.

But a healthy small church is not a quantitative entity. It is fundamentally, frustratingly qualitative. Meaning, it ain't how much you got. It's the character of what you've got. You measure the health of church in the way that you measure the health of families, or of relationships, or of communities.

Or music. Or art. Or a sunset. Or the effect your baby has on you when it first smiles at you.

This cannot be quantified.

Quantitative assessments of those things miss their point completely. No, it's worse than that. They destroy the thing they attempt to assess. They are the wrong tool for the task. Applying empirical measures to the things that give joy is as misguided as brushing your teeth with a claw hammer.

This frustrates those who'd approach church leadership as lightly baptized business management, but honey, it's all about the quality. The health, strength, and purpose of any church rests in quality, which is notoriously hard to quantify.

Wait, you say. Big churches are institutions, with complex structures. Maybe in your little Jesus tribe of a church, qualitative measures matter. But Large needs Quantitative. Leaders of the large must focus on their organizational dashboards! They must have metrics! They must manage!

To which, I would say, look at Pope Francis.

Pope Francis is fascinating. Here in DC, it's like the Fab Four showed up in town, a Pope being received as a celebrity. But not just a celebrity. A Holy Man, someone of unblemished goodness, a beneficent soul, the Papa Di Tutti Papas. That's the buzz, anyway.

But what makes Francis so wildly intriguing to me is that he's really no different from Benedict.

Honestly, he's not, not quantitatively. I followed Benedict closely during his tenure, and he said exactly what Francis has said about capitalism, science, and the environment. Benedict talked in the same way about abuses within the church, and acted to oppose them. I did not always agree with him, but I had a profound respect for his intent, his intelligence, a respect that was deepened when he had the wisdom to step down once he knew he was compromised.

Francis and Benedict, in terms of policy and theology, were remarkably similar. There is almost no difference. Quantitatively, that is.

The difference is tonal and qualitative. Francis understands, instinctively, what faith leadership is all about. It's about manifesting a particular value into the world, in your person. It's about the care of little details--not management details, but interpersonal details. The feeling of a relationship. The timbre of a voice. The twinkle of an eye. A genuine laugh, or a long hug. Loving others, in a way they can feel. Those things are hard to teach. They are not the stuff of tests and metrics. They're the stuff of soul work and personal transformation.

These things matter in the small church. They are its life and breath.

But they are also the heart of every church, at every size. Look at the impact Francis has had on his little church, if you doubt me.

The Way we walk is qualitative.

When the leaders of the church forget this, the heart of the church dies.

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

The Rise of Sharia Law in America

On the American right these days, there's a great deal of talk about "sharia law," the legal code of Islam.

There's fulminating about the insidious power of religious law, taking over the country.

The truth goes deeper. Because there are communities of immigrants who have been living under religious law for centuries, right here in America.

I can tell you, from direct personal experience, that these systems of religious law came here with immigrants and have burrowed in, right here in America, working their subtle subversions. These cells of religious zealots from a barbarous, violent land have chosen not to use the legal system enshrined in our national and state constitutions to settle their disputes.

Instead, they have their own arcane laws, rooted in the strange ways of their peculiar faith. They mete out their own punishments, none of which have anything to do with the Constitution of the United States of America, or with state or local laws. They convene their own courts, which pass judgment and inflict sentences on others. Those courts are answerable to no-one but these zealots, a law unto themselves.

Who are these subversives, who defy the Constitution with their perverse theocratic system of "laws?"

You know who they are, and so do I.

I am speaking, of course, of Presbyterians.

I live under such a system. We Presbyterians have our own laws, and our own courts, our own approach to due process, and our own penal code.

It's in a section of our Constitution called the Rules of Discipline, and we use it to settle disputes and issues within our churches.

It's actually kind of a scriptural mandate, if you read your Bible. Christians shouldn't sue one another, or use the court system to handle disputes. You do that internally, working it out among one another.

And so we do. Or should. The siren song of lawyering up is hard to escape sometimes.

In that, we're no different from our Methodist or Episcopalian brethren and sistren. We're no different from nondenominational sorts, who discipline their members, or from Latter Day Saints, or from Orthodox Jews, or any other of the flavors of American religion.

That's been a part of religious life in America since there was religious life in America.

Of course, those courts have only what power you allow them to have over you. You are free, at any point in the process, to say, "You have no power over me." And with that, the spell is broken.

No one gets executed or imprisoned for violating church law. No-one gets flogged or locked into stocks in the public square. There was a time when Christian courts did this. That's why people came to America--to get away from that mess.

It's why, frankly, so many Muslims are coming to America. First Amendment freedoms are what makes this country worth coming to.

We know this. And yet, as Muslims move to America seeking the freedom to practice their faith without fear, the existence of "sharia" courts has become an implement in the hands of the fear-mongering reactionary right wing. "Look at these Muslims, bringing their sharia courts to America! Sharia law! Unamerican!"

But here, that looks different. You can have a court. You can adjudicate disputes. But the only power you have is the power that all parties freely give. No one gets stoned to death. No one gets beaten. Muslims, here, are doing no more and no less than Christians and Jews do here.

As is their Constitutional right.

There is no reason -- no sane, authentically American reason -- to feel even faintly threatened by this.

There's fulminating about the insidious power of religious law, taking over the country.

The truth goes deeper. Because there are communities of immigrants who have been living under religious law for centuries, right here in America.

I can tell you, from direct personal experience, that these systems of religious law came here with immigrants and have burrowed in, right here in America, working their subtle subversions. These cells of religious zealots from a barbarous, violent land have chosen not to use the legal system enshrined in our national and state constitutions to settle their disputes.

Instead, they have their own arcane laws, rooted in the strange ways of their peculiar faith. They mete out their own punishments, none of which have anything to do with the Constitution of the United States of America, or with state or local laws. They convene their own courts, which pass judgment and inflict sentences on others. Those courts are answerable to no-one but these zealots, a law unto themselves.

Who are these subversives, who defy the Constitution with their perverse theocratic system of "laws?"

You know who they are, and so do I.

I am speaking, of course, of Presbyterians.

I live under such a system. We Presbyterians have our own laws, and our own courts, our own approach to due process, and our own penal code.

It's in a section of our Constitution called the Rules of Discipline, and we use it to settle disputes and issues within our churches.

It's actually kind of a scriptural mandate, if you read your Bible. Christians shouldn't sue one another, or use the court system to handle disputes. You do that internally, working it out among one another.

And so we do. Or should. The siren song of lawyering up is hard to escape sometimes.

In that, we're no different from our Methodist or Episcopalian brethren and sistren. We're no different from nondenominational sorts, who discipline their members, or from Latter Day Saints, or from Orthodox Jews, or any other of the flavors of American religion.

That's been a part of religious life in America since there was religious life in America.

Of course, those courts have only what power you allow them to have over you. You are free, at any point in the process, to say, "You have no power over me." And with that, the spell is broken.

No one gets executed or imprisoned for violating church law. No-one gets flogged or locked into stocks in the public square. There was a time when Christian courts did this. That's why people came to America--to get away from that mess.

It's why, frankly, so many Muslims are coming to America. First Amendment freedoms are what makes this country worth coming to.

We know this. And yet, as Muslims move to America seeking the freedom to practice their faith without fear, the existence of "sharia" courts has become an implement in the hands of the fear-mongering reactionary right wing. "Look at these Muslims, bringing their sharia courts to America! Sharia law! Unamerican!"

But here, that looks different. You can have a court. You can adjudicate disputes. But the only power you have is the power that all parties freely give. No one gets stoned to death. No one gets beaten. Muslims, here, are doing no more and no less than Christians and Jews do here.

As is their Constitutional right.

There is no reason -- no sane, authentically American reason -- to feel even faintly threatened by this.

Monday, September 21, 2015

Faith, Privilege, and Power

Privilege is such a peculiar concept.

And in those ancient witnesses, a truth: privilege is power, power to act, power to make change. Reflexively attacking every manifestation of power only impedes transformation.

If you find yourself with power, and you do not use it for good but instead spend all your energies deconstructing it, how does that serve the cause of justice?

It's the buzzword of the day, the mantra of the earnest, well-meaning left, and on many levels, I get it. But on others, well, the concept seems peculiar. For example, there's an exercise out there now called the Privilege Walk, in which participants are encouraged to take steps forward or back based on a set of criteria. Are you white? Step forward. Did your parents divorce? Step back. Are you college educated? Step forward. Have you ever not been able to afford medical care? Step back. The goal: "illuminate privilege."

What "privilege" entails varies depending on the version of the exercise. Some versions are oriented towards gender/queer issues. Others focus on race. Usually, there's a filter of socioeconomic status. In almost all of the versions I've encountered, I am at or close to the front.

This is not surprising. I am, "white," male, straight, raised by two loving parents, educated, the upper end of middle class, all those things. What I wonder, looking at that exercise, is just what organizers figure will happen next.

After such an exercise, there will be discussions, sure, and people will feel resentful and helpless or guilty and helpless. And there will be more discussions, and participants will feel more divided and less unified. But will those conversations do anything, other than heighten anxiety?

No. No they won't. Heightening anxiety is their primary purpose. They are deconstructive, in the matter of all academe. There can be a place for that, but it's limited. If all you know how to do is tear down, you will never build anything.

"Check your privilege," or so the saying goes, and in some ways it's helpful. I don't get pulled over for driving while black, for example. I don't fear for my safety while walking at night. I don't get harassed because I look sorta generically Middle Eastern. I don't worry about financial ruin if I get sick. If I did not recognize that my reality is not the norm for others, I'd be a fool.

But in mindlessly applying that principle to everything, "progressives" sabotage progress.

The issue with being "privileged" is that an unbalanced culture gives rights to some, and denies them to others. If I can interact with law enforcement officers with confidence, speak and move without fear, then that isn't something I need to "check." It's something I need to share, in the way that knowledge must be shared. I need to press for justice for those who are denied those same, inalienable rights.

And while the imbalances of unjust privileging are worth fighting, privilege itself is something misused by deconstruction. Privilege is the absence of oppression, and in that it is power. As power, it can be used used rightly in a culture. Privilege can bring about change.

If privilege has given you the right to speak without fear, and the right to be heard, and the ability to stand against oppression unchallenged, then that is to be used.

Within the aeons of sacred story rising from my faith, there are examples of those who used privilege rightly.

There's Isaiah, the poet-prophet whose tradition sings furious against the imbalance of economic power and worldly privilege. But Isaiah himself was a man in a position of power. He moved among the Jerusalem elite. He had the ear and the respect of kings. He was, as they say, privileged... meaning he could speak truth without fear and be heard by power.

From his position, he challenged the economic imbalances of urbanization, and the power imbalances that served the privileged elite.

And sure, he could have checked himself, but the call for justice would have been lessened without his voice.

Or Paul, Paul the educated, rhetorically gifted, classically trained apostle. Paul--not his culturally conformed disciples, but the soul that gave us the Seven Letters--spread Christ's message of a radically egalitarian form of being, which fundamentally subverted the power dynamics of Greco-Roman society. And yet when that power came for him, he didn't recoil from his identity as a Roman citizen. He used it to face down power, to push back against power with its own strength.

"Do you realize I'm a full Roman citizen," he'd say, and those who'd imprisoned or beaten him would blanch.

He knew he was a bearer of privilege, and knew how to use it to sabotage privilege itself.

No. No they won't. Heightening anxiety is their primary purpose. They are deconstructive, in the matter of all academe. There can be a place for that, but it's limited. If all you know how to do is tear down, you will never build anything.

"Check your privilege," or so the saying goes, and in some ways it's helpful. I don't get pulled over for driving while black, for example. I don't fear for my safety while walking at night. I don't get harassed because I look sorta generically Middle Eastern. I don't worry about financial ruin if I get sick. If I did not recognize that my reality is not the norm for others, I'd be a fool.

But in mindlessly applying that principle to everything, "progressives" sabotage progress.

The issue with being "privileged" is that an unbalanced culture gives rights to some, and denies them to others. If I can interact with law enforcement officers with confidence, speak and move without fear, then that isn't something I need to "check." It's something I need to share, in the way that knowledge must be shared. I need to press for justice for those who are denied those same, inalienable rights.

And while the imbalances of unjust privileging are worth fighting, privilege itself is something misused by deconstruction. Privilege is the absence of oppression, and in that it is power. As power, it can be used used rightly in a culture. Privilege can bring about change.

If privilege has given you the right to speak without fear, and the right to be heard, and the ability to stand against oppression unchallenged, then that is to be used.

Within the aeons of sacred story rising from my faith, there are examples of those who used privilege rightly.

There's Isaiah, the poet-prophet whose tradition sings furious against the imbalance of economic power and worldly privilege. But Isaiah himself was a man in a position of power. He moved among the Jerusalem elite. He had the ear and the respect of kings. He was, as they say, privileged... meaning he could speak truth without fear and be heard by power.

From his position, he challenged the economic imbalances of urbanization, and the power imbalances that served the privileged elite.

And sure, he could have checked himself, but the call for justice would have been lessened without his voice.

Or Paul, Paul the educated, rhetorically gifted, classically trained apostle. Paul--not his culturally conformed disciples, but the soul that gave us the Seven Letters--spread Christ's message of a radically egalitarian form of being, which fundamentally subverted the power dynamics of Greco-Roman society. And yet when that power came for him, he didn't recoil from his identity as a Roman citizen. He used it to face down power, to push back against power with its own strength.

"Do you realize I'm a full Roman citizen," he'd say, and those who'd imprisoned or beaten him would blanch.

He knew he was a bearer of privilege, and knew how to use it to sabotage privilege itself.

And in those ancient witnesses, a truth: privilege is power, power to act, power to make change. Reflexively attacking every manifestation of power only impedes transformation.

If you find yourself with power, and you do not use it for good but instead spend all your energies deconstructing it, how does that serve the cause of justice?

Saturday, September 19, 2015

Impermanence Imbued with Presence

Early in the morning, as the day was dawning, the flatbed showed up and took away our van.

It was a good old van, a white 2002 Honda Odyssey, bought very lightly used thirteen years ago. Nothing fancy. Nothing special. Just a thing.

There is nothing more practical and perfect than a van.

And after all that time, it still ran like a top. Sure, a few dings here and there, and the rust spots and scrapes of a decade. But as we watched it driving gamely up onto the back of the flatbed, donated to a wonderful charity that gives reliable vehicles to families that need transportation, we knew it'd serve another family well.

We'd replaced it, because we've been blessed enough to be able to get another van. Used, again, of course.

Letting it go was interesting, because though it's just an object, and a relatively generic one at that, it's imbued with memories.

For a quarter of my ever lengthening life, it was present. It was the van that shuttled kids back and forth to an endless stream events, that took us on long road-trip vacations. To the beach. To the lake. To ski. Across state and national borders.

My older son sat in his car seat as we listened to Bert and Ernie sing. A decade and change later, it was the vehicle in which he learned to drive.

I sat with the boys in the back, doubly sheltered by the hatch and the carport, as we watched the trees shake and rock while Hurricane Isabel blasted through.

Seats lowered and removed, it has carried mulch and bricks and dryers, or the futons of friends on the move. Seats up, it has been filled with children and grandparents, or packed with an entire birthday party full of 13 year old boys on their way to ice cream and laser tag.

It drove back and forth to schools, and to concerts, and to swim meets, and to drum lessons, for hours upon hours, days upon days, the equivalent of four times around the planet. Assuming an average of 35 miles an hour, we spent an average of one hundred and twenty one entire days in that van.

It's given so many memories, yet is is not a place or a home but close, a capsule in which the souls that make a place home moved and journeyed.

And now, it's gone, as the things we suffuse with our presence do go.

Letting it go was interesting, because though it's just an object, and a relatively generic one at that, it's imbued with memories.

For a quarter of my ever lengthening life, it was present. It was the van that shuttled kids back and forth to an endless stream events, that took us on long road-trip vacations. To the beach. To the lake. To ski. Across state and national borders.

My older son sat in his car seat as we listened to Bert and Ernie sing. A decade and change later, it was the vehicle in which he learned to drive.

I sat with the boys in the back, doubly sheltered by the hatch and the carport, as we watched the trees shake and rock while Hurricane Isabel blasted through.

Seats lowered and removed, it has carried mulch and bricks and dryers, or the futons of friends on the move. Seats up, it has been filled with children and grandparents, or packed with an entire birthday party full of 13 year old boys on their way to ice cream and laser tag.

It drove back and forth to schools, and to concerts, and to swim meets, and to drum lessons, for hours upon hours, days upon days, the equivalent of four times around the planet. Assuming an average of 35 miles an hour, we spent an average of one hundred and twenty one entire days in that van.

It's given so many memories, yet is is not a place or a home but close, a capsule in which the souls that make a place home moved and journeyed.

And now, it's gone, as the things we suffuse with our presence do go.

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

If It All Came Out Even

An unused remnant from my sermon research a couple of weeks ago stuck around in my head, a peculiar datapoint about faith, wealth and poverty.

It came out of my challenging an assumption I've had for a while about globalization. My assumption, rather simply, had been this: the process of globalizing our economy means that the economies of formerly industrialized nations like the United States are slowly "leaking" into the broader world economy.

Meaning, in fifty years, there will be no difference between the average American and the average Indian. Or the average Mexican. Everywhere, the rich will be just as rich. The global elite look pretty much the same, wherever you find them. But the average person will have...well...what?

I looked around for the primary datapoint relevant to a globalized economy: the Global World Product. How big is the planetary economy, when you fold in everything humans do everywhere?

It's not something that's regularly out there as part of conversation, as we still--stupidly--think in terms of nation-states and localized economies.

I found the data on Wikipedia, of course. $87 trillion in US dollars as of the last year it was calculated, or so the impossibly vast numbers run.

As that's currently divided up, with the lion's share going to the rich, we know what it looks like. But what if it was all divvied up equally?

I assumed that we'd all be barely above the poverty line. From the grasping anxiety of my privileged position, I assumed it would be a disaster, because really, when you get down to it, surely there's not enough to go around.

What surprised me was that there is.

If we divided the Global World Product up even-steven, everyone getting exactly the same share, in 2014 my datasource tells me it would have come out to $16,100 United States dollars per human being. That's sixteen thousand one hundred dollars per soul, $16k for every man, woman, and child on the planet.

Hey, you say. I don't like the sound of that. That information probably was fed into wikipedia from some commie leftist. Bernie Sanders, most likely.

It's from the United States Central Intelligence Agency's World Factbook. Buncha pinkos.

Huh, I thought. Because looking at my household, the four of us could live on that. Sixty four thousand, four hundred bucks? It's way less than we make now, but we'd get by. Totally. No problem. Not so many years back, we had two kids, two nonprofit jobs, and made less than that as a family.

It'd get hard, as the boys grew up and moved on, but we'd figure out a way. Life would go on. We'd learn to work together, and how to pool our resources. We'd neither freeze to death in winter nor starve.

For the average American, it'd be a hit. At 2.58 persons per household on average, that yields an average household income of $41,538, about a 20 percent hit from our current average household average of $51,939. Honestly? Dude, that's completely doable. Here in the DC area, where your debt dollars have fueled a huge surge in the cost of living, that might seem untenable. But average folks in Alabama seem to manage it.

Because then I thought of the billions who do starve, the billions who struggle in backbreaking labor in dry, grudging fields. I thought of those who work insane hours in the globalized factory floors of Asia, doing the work that used to provide for middle class American incomes for a tiny fraction of the wage.

For a Sudanese, what would $16,100 a year mean, if it was everyone in their household? It'd be ten times the average. For a Bangladeshi? Fifteen times the average. For the average Chinese worker? Four times as much. It'd make the difference, night and day.

In the event the robots took over and imposed such a system, we'd pitch a major hissy. It wouldn't be fair, of course. What about the lazy goodfernuthin's who don't deserve it? What about the vaunted creatives and producers? Don't they deserve so very much more? In the metric of our worldly economy, sure. That's how they run this planet.

But I wonder if our resistance has to do with "fairness." Does it reflect our real needs? Or is it a factor of our jealous hungers, and the wild imbalance of our system?

And I was reminded of Jesus, asking us to pray for our daily bread, for only what we really need. No, what we REALLY need. Not our wants. Not what we're used to, or have been taught to expect.

And I was reminded of Jesus, and that crazy commie story about laborers in the vineyard, the one he told about how in the Kingdom we're all the same.

Because the Kingdom economy and the economy of the flesh are very, very different things.

It came out of my challenging an assumption I've had for a while about globalization. My assumption, rather simply, had been this: the process of globalizing our economy means that the economies of formerly industrialized nations like the United States are slowly "leaking" into the broader world economy.

Meaning, in fifty years, there will be no difference between the average American and the average Indian. Or the average Mexican. Everywhere, the rich will be just as rich. The global elite look pretty much the same, wherever you find them. But the average person will have...well...what?

I looked around for the primary datapoint relevant to a globalized economy: the Global World Product. How big is the planetary economy, when you fold in everything humans do everywhere?

It's not something that's regularly out there as part of conversation, as we still--stupidly--think in terms of nation-states and localized economies.

I found the data on Wikipedia, of course. $87 trillion in US dollars as of the last year it was calculated, or so the impossibly vast numbers run.

As that's currently divided up, with the lion's share going to the rich, we know what it looks like. But what if it was all divvied up equally?

I assumed that we'd all be barely above the poverty line. From the grasping anxiety of my privileged position, I assumed it would be a disaster, because really, when you get down to it, surely there's not enough to go around.

What surprised me was that there is.

If we divided the Global World Product up even-steven, everyone getting exactly the same share, in 2014 my datasource tells me it would have come out to $16,100 United States dollars per human being. That's sixteen thousand one hundred dollars per soul, $16k for every man, woman, and child on the planet.

Hey, you say. I don't like the sound of that. That information probably was fed into wikipedia from some commie leftist. Bernie Sanders, most likely.

It's from the United States Central Intelligence Agency's World Factbook. Buncha pinkos.

Huh, I thought. Because looking at my household, the four of us could live on that. Sixty four thousand, four hundred bucks? It's way less than we make now, but we'd get by. Totally. No problem. Not so many years back, we had two kids, two nonprofit jobs, and made less than that as a family.

It'd get hard, as the boys grew up and moved on, but we'd figure out a way. Life would go on. We'd learn to work together, and how to pool our resources. We'd neither freeze to death in winter nor starve.

For the average American, it'd be a hit. At 2.58 persons per household on average, that yields an average household income of $41,538, about a 20 percent hit from our current average household average of $51,939. Honestly? Dude, that's completely doable. Here in the DC area, where your debt dollars have fueled a huge surge in the cost of living, that might seem untenable. But average folks in Alabama seem to manage it.

Because then I thought of the billions who do starve, the billions who struggle in backbreaking labor in dry, grudging fields. I thought of those who work insane hours in the globalized factory floors of Asia, doing the work that used to provide for middle class American incomes for a tiny fraction of the wage.

For a Sudanese, what would $16,100 a year mean, if it was everyone in their household? It'd be ten times the average. For a Bangladeshi? Fifteen times the average. For the average Chinese worker? Four times as much. It'd make the difference, night and day.

In the event the robots took over and imposed such a system, we'd pitch a major hissy. It wouldn't be fair, of course. What about the lazy goodfernuthin's who don't deserve it? What about the vaunted creatives and producers? Don't they deserve so very much more? In the metric of our worldly economy, sure. That's how they run this planet.

But I wonder if our resistance has to do with "fairness." Does it reflect our real needs? Or is it a factor of our jealous hungers, and the wild imbalance of our system?

And I was reminded of Jesus, asking us to pray for our daily bread, for only what we really need. No, what we REALLY need. Not our wants. Not what we're used to, or have been taught to expect.

And I was reminded of Jesus, and that crazy commie story about laborers in the vineyard, the one he told about how in the Kingdom we're all the same.

Because the Kingdom economy and the economy of the flesh are very, very different things.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

The Shamans of Mammon

Seminary, honestly, doesn't quite cut it on that front, which may be one of the challenges facing institutional Christianity. The soul-searing fires of truly untamed places bear little resemblance to the infant-seat trigger-warning-label ethos of academe these days.

But engaging the powers doesn't mean that a shaman is the bearer of a good truth, or the carrier of a healing grace. Sometimes, they're just nuts, their mind blasted into fragments by the merciless desert sun. Other times, they've encountered a reality that has consumed their soul, rendering them a servant of some outer darkness.

The shaman is no more inherently good than any other cleric. Just 'cause you're in touch with the primal chaos doesn't mean you're good, as any book-and-dice Dungeons and Dragons player could tell you.

I was reminded of this recently after doing some sermon research, during which I encountered a bizarre little article on the Guardian, which tends towards the peculiar and the left. It was a reflection on the part of Camille Henrot, a French artist, who articulated in a very arty way her awe at the wonder that was Nicki Minaj.

Nicki Minaj, in the event you're as marginally clued in to popular culture as I am, is a rapper/starlet/hiphop person. Her music, which seems to demand quote marks around it, is like the "music" of Kei$ha or Iggy Azalea. It's hypersexual, radically consumerist, aggressively profane, and airbrush/surgeried/polished to a high gloss by the folks at Corporate.

For Henrot, Nicki Minaj is a "feminist icon," who is "radical" and "majestic." She's "challenging archetypes" and demanding that we abandon our repression of female sexuality. Her music and performances...which you can watch here, if you so choose...are nothing more than the expressions of a "wild woman" and a "shaman."

On the one hand, this kind of abstraction is why feminism is failing as a movement. As it has moved from the practicality of empowerment to the existential distance of academic discourse, it has become less and less capable of critiquing power, of assessing the impact of capitalist semiotics on both action and worldview.

It's not that she's in touch with the primal power of a wild woman's sexuality. There are rappers who do that, dangerously, in a way that's real. There are artists who exist on the margins, drawing their power from their connection to the Wild. That is not Nicki Minaj. She lies at the heart of economic power.

Nicki Minaj is a brand. Nicki Minaj is a product. She's a creature of consumerist objectification. Her sexuality has been marketized and commodified by corporate power. But to observe this radiantly obvious reality? It's "slut-shaming." It's denigrating the integrity of "sex work."

Capitalism, quite frankly, has no beef with academic feminism, because popularized lumpenfeminism has created an ethos in which capitalism can thrive. Corporate capitalism quite happily adapts to the ethos of moral and cultural relativism, to a worldview that breaks humanity up into endlessly smaller categories. Who's to say anyone has the right to judge anyone else's actions? If I define my empowerment by my Bentley and my G4, and use my sexuality to sell myself, what right to you have to go hatin'?

And the alphabet soup of gender studies? Gay? Lesbian? Trans? Genderqueer? Cis? When you get right down to it, they're all just target demographics, baby. It's Marketing 101. Just keep 'em arguing on twitter, and fangrrling about entertainment product, and we're looking at another profitable quarter.

And on the other hand, something about Henrot's observation resonated, if I was honest with myself.

Perhaps, I think, perhaps she is right. Particularly about the shaman thing.

All those musicians who sing the joys of loveless commodified sexuality, of the endless grasping hunger that makes others into objects to be used? Those artists who have been subsumed into the power of the Market, where art serves the fierce power of Wealth? They stand in encounter with that fire, and they have been changed by it.

Perhaps they are the shamanic power of Mammon, being ridden like a malevolent orisha riding a babalao, bearers of the primal churning hunger of concupiscent samsara. Or, to be more accurate, ConcupiSamsara, Inc.

Because there are powers out there in the wildness, and they need someone to sing their songs and tell their stories.

Friday, September 11, 2015

When Power Coopts Our Faith

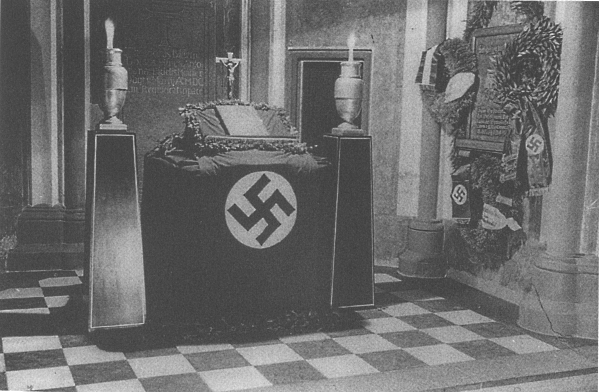

My recent reading of Adolph Hitler's Mein Kampf was difficult, for a range of reasons.

The first of those was, unsurprisingly, his complete and utter hatred of the Jews. Knowing what came of that, for any not-evil human being, that's hard enough to read.

But as a Presbyterian pastor with a Jewish wife and children, it made wading through this monstrous book particularly difficult. Here, a man who would given half a chance have murdered my children, and killed my family. Five hundred and twelve times in that godforsaken book, he spits out his hate, hate on almost every page, a hatred for everything Jewish that is deeply, pervasively demonic.

And here I was, spending time in his mind, and engaging with his thoughts, hundreds and hundreds of pages of them. I felt like Socrates, half-empty cup in hand. My soul recognized the bitter evil of it, tasted that it is toxic. But still, on I drank, forcing myself to take it down, to know it more intimately.

As a person of faith, I tasted in his writing something of the faith that motivated Adolph Hitler. And he did talk a great deal about faith.

Judaism, as far as Hitler was concerned, was not a faith. His hatred of the Jews was not because it was a different religion. As far as he is concerned, it was not a faith at all. He dismisses that as a lie told by liberals, a secret back door to allowing Jews to be just one belief system among many in a pluralistic culture, rather than the source of all evil that Hitler endlessly, relentlessly claimed. Jews, Hitler argues in Mein Kampf, are only a nation and a race, bound together not by a legitimate covenant with God, but by blood and ethnic identity. Given how oddly this sounds against ongoing conversations within Judaism itself about what constitutes Jewish identity, it was peculiar to hear what Judaism's greatest enemy had to say.

Just as hard for me, as a follower of Jesus of Nazareth, was the way that Adolph Hitler coopted the language of Christianity into his service. He uses Christian language and symbol as a way to cement his political power.

On multiple occasions, Mein Kampf coopts the New Testament, using images and snippets from the parables and storytelling of Jesus to make a point.

"Like a camel through the eye of a needle," Hitler says. "No man can serve two masters," Hitler says. I wince at the references, familiar from the voice of my own Master. And of course, he uses the "cleansing of the Temple" image, the go-to Jesus-story for people who want justification for their hatred and desire for violence.

But the references are warped. For example, Hitler was using the camel/needle story in Mein Kampf not to challenge wealth and power as Jesus did, but to attack the idea that representative democracy can ever produce strong leadership. The cleansing of the temple? For Hitler, it's about how Jesus--the Jew, who taught other Jews like a rabbi and used the Torah and the prophets as his foundation--wanted to purge the world of all things Jewish. Hitler's misusage was insane. It had nothing at all to do with the Gospel or Jesus of Nazareth.

Because Adolph Hitler's faith was in martial power, national pride, and cultural purity. That was his god, the object of his worship, the teleological yearning of his mad, misbegotten Reich. The shallow cultural Christianity of the German people was just a means to that ultimate end.

But tapping that source of power worked, clearly, in a potent way. What it did was take the in-group language of Christian faith, and said: look, I know how to speak this way. Look at how I am just like you, about how I share what you share.

He stripped the words away from the reality towards which they were intended to point. No longer do they declare a Kingdom of grace, where the outcasts are welcomed, and the broken are made whole. Hitler uses them and warps them to point to another reality, a darker one, seething with nationalist resentment, racial pride, and violence, the antithesis of the Gospel.

Some Christians realized this demonic influence, and fought it. They were few in number, and died for their resistance. My own Presbyterian denomination remembers their witness, recorded in the Barmen Declaration, as part of our Constitution. It stands as reminder of the terrible danger of allowing our faith to be coopted by political power. Never again, we say, and we keep that memory close and precious.

My reading of the most potently evil book of the twentieth century reminded me of how careful we need to be, as power seeks to take, corrupt, and use the language of our faith to control us.

And right now, we need to be very, very careful.

The first of those was, unsurprisingly, his complete and utter hatred of the Jews. Knowing what came of that, for any not-evil human being, that's hard enough to read.

But as a Presbyterian pastor with a Jewish wife and children, it made wading through this monstrous book particularly difficult. Here, a man who would given half a chance have murdered my children, and killed my family. Five hundred and twelve times in that godforsaken book, he spits out his hate, hate on almost every page, a hatred for everything Jewish that is deeply, pervasively demonic.

And here I was, spending time in his mind, and engaging with his thoughts, hundreds and hundreds of pages of them. I felt like Socrates, half-empty cup in hand. My soul recognized the bitter evil of it, tasted that it is toxic. But still, on I drank, forcing myself to take it down, to know it more intimately.

As a person of faith, I tasted in his writing something of the faith that motivated Adolph Hitler. And he did talk a great deal about faith.

Judaism, as far as Hitler was concerned, was not a faith. His hatred of the Jews was not because it was a different religion. As far as he is concerned, it was not a faith at all. He dismisses that as a lie told by liberals, a secret back door to allowing Jews to be just one belief system among many in a pluralistic culture, rather than the source of all evil that Hitler endlessly, relentlessly claimed. Jews, Hitler argues in Mein Kampf, are only a nation and a race, bound together not by a legitimate covenant with God, but by blood and ethnic identity. Given how oddly this sounds against ongoing conversations within Judaism itself about what constitutes Jewish identity, it was peculiar to hear what Judaism's greatest enemy had to say.

Just as hard for me, as a follower of Jesus of Nazareth, was the way that Adolph Hitler coopted the language of Christianity into his service. He uses Christian language and symbol as a way to cement his political power.

On multiple occasions, Mein Kampf coopts the New Testament, using images and snippets from the parables and storytelling of Jesus to make a point.

"Like a camel through the eye of a needle," Hitler says. "No man can serve two masters," Hitler says. I wince at the references, familiar from the voice of my own Master. And of course, he uses the "cleansing of the Temple" image, the go-to Jesus-story for people who want justification for their hatred and desire for violence.

But the references are warped. For example, Hitler was using the camel/needle story in Mein Kampf not to challenge wealth and power as Jesus did, but to attack the idea that representative democracy can ever produce strong leadership. The cleansing of the temple? For Hitler, it's about how Jesus--the Jew, who taught other Jews like a rabbi and used the Torah and the prophets as his foundation--wanted to purge the world of all things Jewish. Hitler's misusage was insane. It had nothing at all to do with the Gospel or Jesus of Nazareth.

Because Adolph Hitler's faith was in martial power, national pride, and cultural purity. That was his god, the object of his worship, the teleological yearning of his mad, misbegotten Reich. The shallow cultural Christianity of the German people was just a means to that ultimate end.

But tapping that source of power worked, clearly, in a potent way. What it did was take the in-group language of Christian faith, and said: look, I know how to speak this way. Look at how I am just like you, about how I share what you share.

He stripped the words away from the reality towards which they were intended to point. No longer do they declare a Kingdom of grace, where the outcasts are welcomed, and the broken are made whole. Hitler uses them and warps them to point to another reality, a darker one, seething with nationalist resentment, racial pride, and violence, the antithesis of the Gospel.

Some Christians realized this demonic influence, and fought it. They were few in number, and died for their resistance. My own Presbyterian denomination remembers their witness, recorded in the Barmen Declaration, as part of our Constitution. It stands as reminder of the terrible danger of allowing our faith to be coopted by political power. Never again, we say, and we keep that memory close and precious.

My reading of the most potently evil book of the twentieth century reminded me of how careful we need to be, as power seeks to take, corrupt, and use the language of our faith to control us.

And right now, we need to be very, very careful.

Thursday, September 10, 2015

Seven Ways You Can Be Like Hitler

Godwin's Law, in the event you've not heard of it, is the debating principle that states that in every argument, eventually someone will accuse their enemies of being a Nazi. "You're just like Hitler," they'll say. "Gay rights advocates are Nazis! Conservative Christians are Nazis! Cops are all Nazis! Hitler banned guns! Being concerned about gun violence makes you a Nazi! Hitler Hitler Hitler! Nazi Nazi Nazi!"

But as much as his name is the go-to insult for any opponent, and being a Nazi is just shorthand for "an opponent I despise," Hitler's National Socialism was a very, very specific thing. It involved discrete patterns of thought. It was a cohesive ideology and way of understanding the world. To understand it, you must know it. You must engage with it.

Ad fons, or so the saying of my Reformed faith goes. "To the foundations," that means. To understand a thing, go to its source.

And so, with that as my purpose, I girded up my loins, invoked a sequence of protective prayers around my soul, and waded into a book I'd never read. It was the bible of National Socialism, the heart of that darkness: Adolph Hitler's Mein Kampf.

For some reason, I'd visualized a pithy little pamphlet filled with terrible aphorisms. Perhaps it was memories of reading Chairman Mao's Little Red Book echoing in my head.

Oh Lord, was I wrong.

Sweet Mary and Joseph, but that book was long. It was huge, and remarkably, amazingly drab. Much of it is dull, interminable political inside baseball, as Hitler rambles on about the Hapsburg dynasty and minutiae of contemporary German/Austrian Parliamentary processes and personalities. In between some remarkably tedious droning, there was the clear seedbed of horror, a fevered, passionate hatred, and the clear conceptual foundations for both war and the systematic extermination of millions of human beings. Mein Kampf is a monstrous book, an evil thing.

Now that I've read it, and taken the spiritual equivalent of a long hot shower, I have a better sense of both the methodology and approach of National Socialism. Here, seven takeaways, a listicle of evil, what it really means to be like Hitler:

1) It's All About the Outrage. At the beating heart of Mein Kampf is umbrage, the absolute certainty that Other People are Responsible for Our Suffering. "Mein Kampf" means "my struggle," and that's what Hitler means for his reader to feel. He...and you, the reader...are in a desperate struggle against a nefarious Other, who is seeking to destroy all that you hold dear.

That Other, in the five hundred and twelve times he names it, are the Jews. But as Hitler himself admits, it does not have to be. It just has to be an enemy, against which a movement or a nation can be organized. As Hitler puts it:

"The art of leadership, as displayed by really great popular leaders in all ages, consists in consolidating the attention of the people against a single adversary and taking care that nothing will split up that attention into sections. The more the militant energies of the people are directed towards one objective the more will new recruits join the movement, attracted by the magnetism of its unified action, and thus the striking power will be all the more enhanced."I've read this before, seen this principle used as a baseline for organizing a mass movement. It's articulated repeatedly in Saul Alinsky's The Rules for Radicals, for pointed example.

To get a people moving, there is nothing more effective than an enemy to demonize and hate.

2) Politicians are All Corrupt. Hitler spends a great deal of time attacking politicians. They are all pocket-lining, incompetent fools, he asserts. All they know how to do is speechify, and none of them do their jobs. They need to be replaced, all of them.

His attacks on politics as usual, through a simple redirection of force, becomes an attack on the idea of representative democracy itself. Our representatives are just suck-ups and weaklings, and that's the only reason they are in power.

"Surely nobody believes that these chosen representatives of the nation are the choice spirits or first-class intellects," he snarks.

Throw the bums out. Having accepted that premise, it's an easy move to Hitler's answer: they need to be replaced by men of Will and Honor, people who can really get done what needs to get done.

By which he means himself, and the Nazi Party.

Hitler was clearly tapping a deep wellspring of popular cynicism about governmental incompetence, and particularly the incompetence of representative government. Sure is a good thing that there's none of that in America these days.

3) The Press is The Enemy. Hitler hated the press. As far as he was concerned, the media were primarily responsible for the collapse of German pride, sappers of the will of the people. Again, he taps a deep and abiding cynicism, this time about the media. For example:

"It took the Press only a few days to transform some ridiculously trivial matter into an issue of national importance, while vital problems were completely ignored or filched and hidden away from public attention."Why does the press do this? Well, it's the "Jewish Press," as far as Hitler is concerned. Because Jews engage in objective thinking, which saps the vital essence of a people. That's the idea, at least.

From that foundation of racial hate and cynicism, Hitler makes the move to asserting...at great length...what the press should be doing.

Hitler argues that the goal and purpose of all media needs to be instilling patriotism and national pride. It must intentionally create propaganda--he's unafraid of that term--that stirs the emotions of the lowest common denominator. It does not matter if this propaganda is "true." It only matters that the people believe it, and that it serves the purpose of patriotic endeavor.

As Hitler puts it, good propaganda is exactly like advertising or marketing. The goal is not to tell the objective truth. It's to sell your product. Or to proclaim your ideology.

The best propaganda, in other words, speaks to the folks in your society who primarily use their lizard brains, whose higher functions are ruled by their passions and emotions.

4) The Military Is the Heart of Culture. Hitler's National Socialism was fascist, and central to fascism is complete reverence for all things military. That's what the fasces--the bundle of sticks with an axe-blade that is the symbol of fascism--represents. Hitler talks, at great length, about the refining fire of martial endeavor, about the nobility of the military and the abuses suffered by veterans. The military is, as far as he is concerned, the very best part of national identity.

Why? Because in the crucible of conflict, where your life is on the line, men become stronger. Or they die. And because this is done in the service of the nation, soldiers are the truest, most tested patriots.

As he presents it, the German army only lost because it was betrayed by the press and subverted by the Jews. It made no errors. It was about to win, until victory was snatched from it by the Other.

He has nothing but contempt for talk of peace. Peace makes a people weak. Those who call for compromise and finding nonviolent solutions with the Enemy are just parasites or subversives.

5) Passion is Primary, Critical Thinking is to be Avoided. The goal of National Socialism is passion, which is peculiar, given the tone and language of Mein Kampf. It's a cold book, bright-eyed and distant, written in a tone that most closely resembles the distant, unforgiving prose of Ayn Rand. It is, itself, a little distant.

For those few in control of the system, being dispassionate is key. The scientists and the elites must be cool, rational thinkers.

Yet for the rest of the people, what Hitler prescribes is passion and emotion. Outrage, yes, but also all other emotions. Fierce love. Tears. Laughter. Joy. The reason for this: motivating the masses. To stir the heart of a folk is to call them to the Great and Noble End which you are pursuing. Make them feel the feels. Stir their heart, because it is from emotion--anger and pride in particular--that the strength of a people is found.

What's remarkable is how up front he is about his methods. Right there in his book, the idea that leaders must manipulate the emotions of their followers, that they should mask objective truth.

6) Liberal Intellectuals are the Enemy. Why? As Hitler describes it, this is because they undermine the spirit of patriotism that shapes a nation's pride and purpose. Liberal intellectuals tend to be internationalists, who see value in other cultures and other races, and this distracts from building up national identity. They also insist on critiquing the behaviors of a nation, which drains morale and the vigor of the folk.

Worse yet, liberals insist on looking for common ground with the Enemy, or finding reasons that the Enemy isn't really as bad as all that.

For example, Hitler has pages of venom directed at those German Christian liberals who argued that Jews were just another faith, and that they could be truly German.

He also notes with rage that liberals had taken charge of the educational system, and that they were using education to corrupt the spirit of German youth. The purpose of education, Hitler suggests, is not to create objective, critical thinkers. It is to teach the greatness of a people, to inculcate pride and patriotism, and to cement their commitment to the national purpose.

7) The Goal Is Purity. What mattered to National Socialism was racial and ideological perfection. That was its goal and purpose. All compromise, accommodation, and weakness were to be cut away.

For Hitler's National Socialism, that meant racial purity. The Aryan and Germanic ideal was only diluted by efforts to blend in or mix with other cultures and races. Efforts to create states that included multiple cultures were inherently doomed, because they were inherently corrupted.

From that also rises a focus on ideological purity. That means that any variance from the party line, any whiff of compromise, any move away from the One Purpose? It is to be viewed as suspect.

National Socialism, as Hitler lays it out in Mein Kampf, represents a radically binary, absolutist worldview. There is Us, and We are Good. And then there is Not-Us, which is inferior or the enemy.

And there, from the darkest heart of twentieth century evil, are seven key features of Hitler's thinking, of what it really means to be a Nazi.

It's important to have a grasp on these principles. Why? Because while Godwin was right about our compulsive overuse of the Nazi/Hitler card, that doesn't mean that there aren't movements and leaders that actually resemble National Socialism.

And just because we falsely cry wolf, over and over again, that doesn't mean that wolves don't still roam hungry in the darkness of our culture, looking for an opportunity to rule.

Labels:

godwins law,

hitler,

nazi,

politics

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

Narrative, Ambiguity, and Apocalypse

As I prepare myself to work on the final edits to my novel, I find myself wrestling with something of a paradox.

What I'm writing is apocalyptic literature, in the most classical sense of the term. As a biblical narrative genre--and yes, it's a biblical narrative genre--apocalyptic literature is intended to open up the eyes of the reader. ἀποκάλυψις, in the Greek, means an "unveiling," a revealing of truths otherwise hidden.

That "revealing" happens when something comes along to shatter conventional reality, as the patterns and norms of our societal power dynamics are obliterated. That can involve zombies, asteroids, and pandemic plagues. It can involve the tearing apart of the heavens, and the arrival of the four horsemen. The core idea is the same.

As a biblical genre, apocalypse reveals the way ahead, the Path That Is God's Will.

I'll freely admit that some Biblical apocalypses don't do that revealing part well. John da Revelatah was notorious for not getting that memo, masking his truths in secret-code language and fever-dream abstractions.

But what he was trying for, what all those who speak in apocalyptic language are trying for, is to open our eyes to the Way Things Are.

In working to refine my manuscript, though, I'm realizing that ambiguity is a necessary part of apocalyptic. As I work with my excellent, capable editor, I find myself trying to keep the narrative as open-ended as possible, struggling create a conclusion that is both satisfying but also allows the reader freedom of interpretation.

Why? Because narratives that only have a single possible outcome reveal nothing. By saying: this is the plan, there is no variance from the plan, and everything will go according to plan, we are masking ourselves with a false certainty.

What does that mean? Hmm. If you give a person only one choice, it tells you nothing about them. "You may only do this," you say. "OK," they say, and they do it. Their choosing that path means nothing, because that is the only path you have left open to them. It does not reveal anything about their nature.

As it stands in relationship to a reader, such a narrative is not apocalyptic.

It is Calyptic literature, literature that masks and veils and hides the truth behind its rigidity. This is what fundamentalist literalism does to the sacred texts of Scripture. It does not test. It does not challenge. It does not do what Jesus did when he taught in parables, which were designed to give the hearer the opportunity to misinterpret them.

But if you say, here you are free to choose, free to interpret, free to act as you wish? Then that choosing reveals a truth about the soul that decides. Do they choose for good or ill or some admixture of the both? Do they choose based on grasping self-interest, or compassion?

Ambiguity may not reveal the One Truth of Reality. But it reveals the truth about anyone who encounters it.

In that, ambiguity is the nature of our apocalypse, the apocalypse that God is working right now.

And that Divine Ambiguity is the fire in which we--as persons, as cultures--are tested and known.

What I'm writing is apocalyptic literature, in the most classical sense of the term. As a biblical narrative genre--and yes, it's a biblical narrative genre--apocalyptic literature is intended to open up the eyes of the reader. ἀποκάλυψις, in the Greek, means an "unveiling," a revealing of truths otherwise hidden.

That "revealing" happens when something comes along to shatter conventional reality, as the patterns and norms of our societal power dynamics are obliterated. That can involve zombies, asteroids, and pandemic plagues. It can involve the tearing apart of the heavens, and the arrival of the four horsemen. The core idea is the same.

As a biblical genre, apocalypse reveals the way ahead, the Path That Is God's Will.

I'll freely admit that some Biblical apocalypses don't do that revealing part well. John da Revelatah was notorious for not getting that memo, masking his truths in secret-code language and fever-dream abstractions.

But what he was trying for, what all those who speak in apocalyptic language are trying for, is to open our eyes to the Way Things Are.

In working to refine my manuscript, though, I'm realizing that ambiguity is a necessary part of apocalyptic. As I work with my excellent, capable editor, I find myself trying to keep the narrative as open-ended as possible, struggling create a conclusion that is both satisfying but also allows the reader freedom of interpretation.

Why? Because narratives that only have a single possible outcome reveal nothing. By saying: this is the plan, there is no variance from the plan, and everything will go according to plan, we are masking ourselves with a false certainty.

What does that mean? Hmm. If you give a person only one choice, it tells you nothing about them. "You may only do this," you say. "OK," they say, and they do it. Their choosing that path means nothing, because that is the only path you have left open to them. It does not reveal anything about their nature.

As it stands in relationship to a reader, such a narrative is not apocalyptic.

It is Calyptic literature, literature that masks and veils and hides the truth behind its rigidity. This is what fundamentalist literalism does to the sacred texts of Scripture. It does not test. It does not challenge. It does not do what Jesus did when he taught in parables, which were designed to give the hearer the opportunity to misinterpret them.

But if you say, here you are free to choose, free to interpret, free to act as you wish? Then that choosing reveals a truth about the soul that decides. Do they choose for good or ill or some admixture of the both? Do they choose based on grasping self-interest, or compassion?

Ambiguity may not reveal the One Truth of Reality. But it reveals the truth about anyone who encounters it.

In that, ambiguity is the nature of our apocalypse, the apocalypse that God is working right now.

And that Divine Ambiguity is the fire in which we--as persons, as cultures--are tested and known.

Sunday, September 6, 2015

What Fighting for Your Religious Freedom Looks Like

Anger, fear, and resentment are wonderful ways to motivate and radicalize a constituency. And so there's an episode in our history, long forgotten to most of America, that's on my mind as the political umbrage machine finds reasons to stir our fears this season.

One of the major rallying cries for this upcoming election is this: Religious freedom is threatened. How? Well, there's an anecdote here, and a snopes-fail story there, but really? All that matters is that people are riled up enough to feel motivated.

And sure, there are real threats to the freedom of religious practice elsewhere. In China, for example, where churches are forced to close for just being churches. Or in the Middle East, where being Christian means you may be tortured and beheaded. Our self-aggrandizing sense of "oppression" is an embarrassment to the faith, a mockery of the very real crosses borne by Christ followers around the world.

"Tyranny?" Lord help us, we have no idea what that means, although the folks who are manipulating our fears would be happy to show us, I'm sure.

That's not to say that religious freedom hasn't been challenged before in the United States. It has. When that's happened, though, and when it was resisted, what did that look like?

What does defending your religious freedom look like in a constitutional republic, when it's genuinely at risk?

For that, my research into the dynamics and lives of the Old Order Amish for my forthcoming novel surfaced an interesting case. There was a time, in the mid-20th century, when the Amish were jailed for their beliefs. It was the era when public education was increasingly a national priority. The United States was in the midst of the Cold War, and them Russkies were edumacating their young 'uns up real good.

If we didn't develop a new generation of scientists and mathematicians and engineers, the Red Menace would overtake us with their Sputniks and their Soyuzes and their ICBMs. Next thing you know, we'd be singing the Internationale, watching terrible propaganda musicals, and being herded into interminable performances of abstract dance at the Bolshoi.

So STEM education was the rule of the day, and everyone needed to be on board. School was mandatory.

But a group of Wisconsin Amish refused to send their kids to school past eighth grade, on religious grounds. They were conservative Christian agrarian/craftsman pacifists, and they wanted to educate their children to be part of their community. They had nothing against literacy, because the Amish were and are avid readers and writers. They had nothing against math, in so far as you need some math to run a farm or a small business or a household.

But the rest of modern-era public higher education was preparing their children for an economy in which they did not want to participate, an economy that was antithetical to their faith. So they refused.

Their children simply didn't show up to class. Or, if forced to go to class, they'd flee into the cornfields. Amish parents were accused of encouraging truancy, of subverting the American way with their backwards ignorance. Charges were filed. The Amish held their ground.

Amish elders were jailed, repeatedly, for breaking the law of the land. They maintained their position, relentlessly and peacefully, with the stubborn gentleness of that movement.

Ultimately, they won. In 1972, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of the Old Order Amish, in a landmark decision establishing the rights of parents to see to the education of their young ones.

But there's a detail in there, one that the current self-absorbed hullabaloo about religious freedom willfully ignores. The Amish were only interested in defending their way of life.

They were not, in any way, imposing their way of life on others.

Let me repeat that, because that's the part we seem confused about:

They were not, in any way, imposing their way of life on others.

I'd bold it and put it in all-caps, but hopefully, that point has been gotten across.

What we "English" do did not matter to them. They had their way, their path, their Ordnung. Others were not expected to live by it, not coerced by the power of the state into living according to their rules.

Now, I'm a fan of public education. Is it perfect? No, of course not. But it's a good thing, a public good, something that makes our nation better. Smarter. Stronger. Faster. Nonetheless, I can respect both the Amish position and the way in which they went about defending their inalienable rights.

In a democratic republic, where your neighbor's freedom matters as much as your own, they showed us how defending religious liberty is done.

One of the major rallying cries for this upcoming election is this: Religious freedom is threatened. How? Well, there's an anecdote here, and a snopes-fail story there, but really? All that matters is that people are riled up enough to feel motivated.

And sure, there are real threats to the freedom of religious practice elsewhere. In China, for example, where churches are forced to close for just being churches. Or in the Middle East, where being Christian means you may be tortured and beheaded. Our self-aggrandizing sense of "oppression" is an embarrassment to the faith, a mockery of the very real crosses borne by Christ followers around the world.

"Tyranny?" Lord help us, we have no idea what that means, although the folks who are manipulating our fears would be happy to show us, I'm sure.

That's not to say that religious freedom hasn't been challenged before in the United States. It has. When that's happened, though, and when it was resisted, what did that look like?

What does defending your religious freedom look like in a constitutional republic, when it's genuinely at risk?

For that, my research into the dynamics and lives of the Old Order Amish for my forthcoming novel surfaced an interesting case. There was a time, in the mid-20th century, when the Amish were jailed for their beliefs. It was the era when public education was increasingly a national priority. The United States was in the midst of the Cold War, and them Russkies were edumacating their young 'uns up real good.

If we didn't develop a new generation of scientists and mathematicians and engineers, the Red Menace would overtake us with their Sputniks and their Soyuzes and their ICBMs. Next thing you know, we'd be singing the Internationale, watching terrible propaganda musicals, and being herded into interminable performances of abstract dance at the Bolshoi.

So STEM education was the rule of the day, and everyone needed to be on board. School was mandatory.

But a group of Wisconsin Amish refused to send their kids to school past eighth grade, on religious grounds. They were conservative Christian agrarian/craftsman pacifists, and they wanted to educate their children to be part of their community. They had nothing against literacy, because the Amish were and are avid readers and writers. They had nothing against math, in so far as you need some math to run a farm or a small business or a household.

But the rest of modern-era public higher education was preparing their children for an economy in which they did not want to participate, an economy that was antithetical to their faith. So they refused.

Their children simply didn't show up to class. Or, if forced to go to class, they'd flee into the cornfields. Amish parents were accused of encouraging truancy, of subverting the American way with their backwards ignorance. Charges were filed. The Amish held their ground.

Amish elders were jailed, repeatedly, for breaking the law of the land. They maintained their position, relentlessly and peacefully, with the stubborn gentleness of that movement.

Ultimately, they won. In 1972, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of the Old Order Amish, in a landmark decision establishing the rights of parents to see to the education of their young ones.

But there's a detail in there, one that the current self-absorbed hullabaloo about religious freedom willfully ignores. The Amish were only interested in defending their way of life.

They were not, in any way, imposing their way of life on others.

Let me repeat that, because that's the part we seem confused about:

They were not, in any way, imposing their way of life on others.

I'd bold it and put it in all-caps, but hopefully, that point has been gotten across.

What we "English" do did not matter to them. They had their way, their path, their Ordnung. Others were not expected to live by it, not coerced by the power of the state into living according to their rules.

Now, I'm a fan of public education. Is it perfect? No, of course not. But it's a good thing, a public good, something that makes our nation better. Smarter. Stronger. Faster. Nonetheless, I can respect both the Amish position and the way in which they went about defending their inalienable rights.

In a democratic republic, where your neighbor's freedom matters as much as your own, they showed us how defending religious liberty is done.

Saturday, September 5, 2015

The Gatekeeper

The truth of the recent Kim Davis mess in Kentucky surfaced in a detail, a detail familiar to anyone who has spent any time around churches.

We've been there, all us Jesus folk, when someone decides they're in charge of something at a church. It could be anything. It could be the coffee hour. Or the treasury. Or the annual Life Day celebration.

This is their thing. Sometimes, it's because they are doing it for the joy of it. It's a way of exuberantly sharing their gifts and graces. Other times, they're doing it with an open hand and a servant heart.

And other times? Well, sometimes there are...cough...other motivations.

They own it. It belongs to them.

That part of the life of the community becomes the place of their power, the place that gives them a sense of control over the world around them. Sure, their life may be a wreck otherwise, a weeping disaster of abandonment and brokenness, failure heaped on failure, but when it comes to determining how the doilies are arranged on the fellowship hall tables, they are the Absolute Ruler of All That May Be Done.

They are the Gatekeeper.

Woe betide anyone who messes with that sense of power. No-one else is allowed to touch it, to do it differently. If you are a new member or a fresh-out-of-seminary pastor, it's a thermonuclear landmine. Mess with their fiefdom, and that Gatekeeper will do everything in their power to destroy you.

Because that role is them, themselves. And sure, it seems so impossibly small a thing to fight over, such a waste of energy over a tiny nothing, But that tiny nothing is the source of their identity, and they're as understanding about your touching it as Sauron was with that little ring of his.

This, I am convinced, is why when the libertarian out was offered, Davis did not take it. Rand Paul, the quasi-libertarian, named it the other day in an interview.

Just have someone who doesn't object to the law sign the documents, like, say, a notary public. Then the law is upheld, the freedom of gays and lesbians is not violated, and her freedom of conscience is not violated. It would also be entirely legal.

That was precisely the compromise offered by the court. OK, fine, the judge said. You don't have to do that. Just authorize someone else to do it. But that compromise was flatly rejected.

And in rejecting it, the truth of her position seems clear. It is not just that she can't perform her duties because it would violate her liberty. It is that she does not want the thing over which she has power done any way other than she wishes it done. It would violate not her own freedom, but her control over the liberty of others.

She has become the Gatekeeper.

Now, it'd be easy at this point to get all self-righteous about how terrible a person she is, what a terrible Christian, to do such a thing.

But this hunger for power rests in all of us, no matter where we are in the political spectrum. We all yearn for it, desire it, that place where our will rules over all. Privilege feeds it. So does the brokenness of want or powerlessness. Whenever we are in community, it whispers to us, or rises up in indignant fury when someone suggests that maybe we might try doing it differently.

That desire, for power over the Other, that concupiscence, is the dark heart of human sin.

Our sin.