Incompetence takes a while to do damage.

In the frothing, bubbling reactiveness to our current administration, that reality gets missed. Everything is a reason to be upset. Whatever minor outrage has been instigated that day consumes the twitching twitter-madness of our twenty four minute news cycle.

Most of it is irrelevant.

What's worth looking at are the real crisis points, the places of genuine threat, where the issue is not just that we're on the wrong road heading the wrong direction at a hundred and twenty with a cheap beer in our hand, but are also at real risk of crashing through a guardrail and into a ravine.

The first of these, it seems, comes in September or October, when the federal government runs out of money. That wouldn't just mean a few federales not getting paid for a bit. It'd mean default, and a cascade that would seize up the Rube Goldberg contraption that passes for our global economy.

That means bad things.

This has happened before, too often, as our debt-addled culture continues to believe it can function by just borrowing, borrowing, borrowing. The way to approach that is through sensible budgeting, streamlining functions of government, really dealing with health care costs, making the wealthy pay their fair share, and standing down our imperial military.

But that would require sanity. And sanity? Hah. The inmates are running Arkham now, and things are different.

The party that controls both houses of Congress? Too many of its members are neo-Confederates, who would be perfectly happy to bring the Union down. They are "led" by a President whose sense of his own skills is as far removed from his actual competence as we are from taking our summer vacations on Kepler 186f.

There is a substantially higher chance that this recurring inflection point will be bungled, through some toxic admixture of blind ideology and brazen stupidity.

And sure, there are grownups in the room, advisors who know how the system works, and know what would happen if a fool convinced that he is the best negotiator who has ever lived decided to use catastrophic default as leverage for renegotiating the debt. Those grownups do not want to pointlessly crater the global economic system, because that would be bad.

The odds are in favor of things just proceeding as normal. Most likely, things will be fine.

But those odds feel markedly lower than they once were, in a way that's faintly distressing. Not panic inducing. Just a little worrying, as you notice some...but not all...of the warning signs. A little worrying, as the numbers look less like "what are the chances I'll be struck by lightning today" and more like "what's the likelihood I'll spill some of my coffee tomorrow morning."

That's the problem trying to be prophetic in a probabilistic universe. "There's a thirty four point two percent chance that the end might possibly be near" just doesn't have the right ring to it.

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

JEB Stuart and the Confederate Cause

Both of my sons have, over the last five years, attended J.E.B. Stuart High School.

The name of the school, honestly, always struck me as a little peculiar. Here, a human being who led raids into the area in and around Washington DC, as his cavalry unit sacked and burned and terrorized Union supporters.

And by Union, I mean American. Because the entity he was attacking was the United States of America. Not "the North." Not "Yankees." But the United States of America.

There's a sustained debate now about the name of their school, and whether J.E.B. Stuart's cause really reflects the values we Americans honor.

Stuart was a Confederate, meaning the cause he fought for was the Confederate States of America. The argument is made, often and with earnestness, that the Confederacy was all about state's rights. From that perspective, the War Between the States was not about slavery, but about the right of states to have their own identity over and against those Federal tyrants in Washington. It's was a fight for local autonomy over semi-imperial control, or so some would still argue, particularly those who have that ideological bent in the first place.

There were, no doubt, Confederate soldiers and officers who believed that was so. That seems self-evident from both history and their writings.

I also do not feel it is necessary to demonize every person who fought for the Confederacy.

I also do not feel it is necessary to demonize every person who fought for the Confederacy.

Decent human beings sometimes fight for monstrous causes. This may fly in the face of the clumsy, shallow echo-chamber dualism of our benighted era, but it has the merit of being real.

However, I am not fool enough to imagine, for a moment, that those human beings were correct in their thinking. Rather, that "gloss" was the self-delusion that permitted good people to serve a demonic purpose.

I once believed that local control was a relevant part of the dynamic that defined the Confederate cause, but I no longer do. States rights were just a rationalization, a saccharine falsehood that many otherwise decent people told themselves to justify their support of a cause that was a fundamental affront to human liberty.

I once believed that local control was a relevant part of the dynamic that defined the Confederate cause, but I no longer do. States rights were just a rationalization, a saccharine falsehood that many otherwise decent people told themselves to justify their support of a cause that was a fundamental affront to human liberty.

The Confederate States of America, as an entity, as a concept, and as a failed state, was entirely and completely about perpetuating the institution of racially based human chattel slavery. Period.

What is the basis for that statement?

Go to the foundations, or so my Presbyterian forebears said, if you want to know the truth of a thing.

As a pastor and follower of Jesus of Nazareth, my self-understanding and the purpose of my faith can be found in the Gospels. Those texts are where you can go to discover what it means to be a Christian. Similarly, as a proud citizen of the United States of America, I find the essence of our republic enshrined in our Constitution and our Declaration of Independence.

And so to understand the Confederacy, we must study their parallel founding documents: the Confederate Constitution and the Declarations of Secession made by the Confederate states to justify their departure from the United States. If this is about the rights of individual states, then that will be clear in the arguments the founders of the Confederacy made.

To the CSA Constitution first.

To the CSA Constitution first.

I had always assumed, as a high school student, that the Confederacy had gone back to some version of the Articles of Confederation for their ruling principles. That first American effort at a defining document was a loose gathering of states, in which the rights of individual states superceded that of the central government. It was too loose a union, ultimately, to be sustained, but the Articles were all about local control. That would have made sense. Heck, it even has Confederation in the name.

The CSA Constitution was not based on that early American document. For their defining text, the leaders of the Confederacy chose to simply copy the Constitution of the United States of America, and then edited it to reflect what they saw to be the primary reasons for their departure.

It is in those editorial choices that the Confederate cause reveals itself.

Those distinctions are best observed by engaging in a line-by-line comparison of the two documents, which can be done by following this link to an excellent and straightforward website that lets you do precisely that.

Do not continue reading until you have followed that link. Seriously. Look at it.

Do not continue reading until you have followed that link. Seriously. Look at it.

As the author highlights, there are some trivial variances, most of which involve taxes and duties on sea and river traffic, line item vetoes, and term limits.

There is the inclusion of an explicit reference to God in the preamble, which seems, in retrospect, to have been something of a mistake. Never, ever invoke God unless you're ready for God to show up.

Remarkably, the Confederate constitution contained no meaningful effort to decentralize authority. None. States in the CSA had no more rights than states in the USA, and in some ways had less. Richmond had as much power as Washington.

But what is written in, repeatedly, and forever enshrined as an inalienable right of citizens of the CSA?

The right of "white" men to own "negro slaves."

In point of fact, states that were part of the CSA could not choose not to be slave-holding. It is explicitly racist and opposed to human freedom as a principle.

But our Constitution is a functional document. For a statement of America's higher principles, it is the Declaration of Independence that lays out more clearly the cause of liberty. What of the Confederate equivalents? For that, we can look at the statements made by the states of Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas.

Seriously. Again, read them. The motivating principle, elucidated variantly but clearly in each of these documents, establishes the primary cause for their departure. That cause? Human chattel slavery, grounded in assumptions of white supremacy.

And, to be more accurate, their indignation that the free states were treating the blacks who fled north seeking freedom as human beings and not property.

Each of those four confederate declarations of secession is completely clear on the matter.

What is inescapable and written in the words of those who established the Confederacy: the cause of their nation, and the primary distinction between it and the United States of America as repeatedly written into the CSA founding documents? The "right" of one human being to own another, grounded in contemptible assumptions of racial superiority. It was, by design, both racist and antithetical to the principles of human liberty that are the best angels of the American spirit.

In point of fact, states that were part of the CSA could not choose not to be slave-holding. It is explicitly racist and opposed to human freedom as a principle.

But our Constitution is a functional document. For a statement of America's higher principles, it is the Declaration of Independence that lays out more clearly the cause of liberty. What of the Confederate equivalents? For that, we can look at the statements made by the states of Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas.

Seriously. Again, read them. The motivating principle, elucidated variantly but clearly in each of these documents, establishes the primary cause for their departure. That cause? Human chattel slavery, grounded in assumptions of white supremacy.

And, to be more accurate, their indignation that the free states were treating the blacks who fled north seeking freedom as human beings and not property.

Each of those four confederate declarations of secession is completely clear on the matter.

What is inescapable and written in the words of those who established the Confederacy: the cause of their nation, and the primary distinction between it and the United States of America as repeatedly written into the CSA founding documents? The "right" of one human being to own another, grounded in contemptible assumptions of racial superiority. It was, by design, both racist and antithetical to the principles of human liberty that are the best angels of the American spirit.

Soldiers like Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stuart may well have been good men in other ways. They may have believed that they were fighting for a just cause.

But they were wrong.

Slavery and racism were the demons of America's founding, standing in irreconcilable dissonance with the principles of liberty and equality that make our nation great.

As our nation takes a hard look at the way we've memorialized those men who fought against the principles of liberty on which our nation was founded, that must be kept front and center.

Slavery and racism were the demons of America's founding, standing in irreconcilable dissonance with the principles of liberty and equality that make our nation great.

As our nation takes a hard look at the way we've memorialized those men who fought against the principles of liberty on which our nation was founded, that must be kept front and center.

Saturday, June 24, 2017

Designed for Failure

It had been a while since I'd messed up that badly.

It was because I was rushing, of course, because catastrophic failure often happens when you're in too much of a hurry to do things right.

There I was, on the Beltway, and it was 100 degrees, heat pouring from the eight lanes of tarmac. I was on my motorcycle, and traffic was grinding slowly towards the American Legion Bridge. I was not wearing my riding boots, but instead, a pair of shoes.

With shoelaces.

The protocol, correctly observed, when riding with long shoelaces on a motorcycle, is to tuck them in. I knew this. I have known this for thirty years of riding. But I was in a rush, and hot, and distracted.

So there I was, stopping and going, sweating in the heat, surrounded by an endless column of cars. I put my foot down. Then moved forward ten yards, my foot coming up. I put my foot down. The cycle repeated, over and over.

Then I moved forward ten yards, and went to put my left foot down. But my laces had wrapped around the shifter pedal. The foot would not go down, not without bringing me and five hundred pounds of motorcycle down with it.

So despite a wild, desperate flailing effort to counterbalance, down I went.

I got disentangled and up quickly, as one does when in encounter with burning hot asphalt, and before I could set my back into the bike and lift with my quads...that, I'd not forgotten...a good soul in a pickup next to me helped me right my scraped steed.

I restarted the bike.

It was then I realized my clutch lever (left side, on the handlebar) had been snapped by the impact. Without it, I could not shift. But it had...fortune of fortunes!...broken high on the lever. There was still enough lever remaining to engage the clutch and shift gears. Had there not been, I would have been left standing in eight lanes of Beltway traffic with an unrideable motorcycle at the height of DC rush hour.

What good luck, I thought.

Only it wasn't, or so I realized when the replacement lever arrived.

The folks at Suzuki had designed both their clutch and brake levers with a cutout in the metal, right at the point where the lever had snapped. Because people drop bikes all the time. Perhaps you're a new rider, and your balance is uncertain. Or you hit a patch of oil or wet leaves or gravel. Or you're just being a distracted, rushing idiot.

So they'd factored that in, making it much more likely that a low speed drop would still leave you with a ridable motorcycle. It was meant to break manageably, meant to fail in a way that was recoverable.

Which is how you design a system, when you actually care about the people who use it. When you don't want one mistake or moment of misfortune to be catastrophic.

I just wish American society was set up the same way.

It was because I was rushing, of course, because catastrophic failure often happens when you're in too much of a hurry to do things right.

There I was, on the Beltway, and it was 100 degrees, heat pouring from the eight lanes of tarmac. I was on my motorcycle, and traffic was grinding slowly towards the American Legion Bridge. I was not wearing my riding boots, but instead, a pair of shoes.

With shoelaces.

The protocol, correctly observed, when riding with long shoelaces on a motorcycle, is to tuck them in. I knew this. I have known this for thirty years of riding. But I was in a rush, and hot, and distracted.

So there I was, stopping and going, sweating in the heat, surrounded by an endless column of cars. I put my foot down. Then moved forward ten yards, my foot coming up. I put my foot down. The cycle repeated, over and over.

Then I moved forward ten yards, and went to put my left foot down. But my laces had wrapped around the shifter pedal. The foot would not go down, not without bringing me and five hundred pounds of motorcycle down with it.

So despite a wild, desperate flailing effort to counterbalance, down I went.

I got disentangled and up quickly, as one does when in encounter with burning hot asphalt, and before I could set my back into the bike and lift with my quads...that, I'd not forgotten...a good soul in a pickup next to me helped me right my scraped steed.

I restarted the bike.

It was then I realized my clutch lever (left side, on the handlebar) had been snapped by the impact. Without it, I could not shift. But it had...fortune of fortunes!...broken high on the lever. There was still enough lever remaining to engage the clutch and shift gears. Had there not been, I would have been left standing in eight lanes of Beltway traffic with an unrideable motorcycle at the height of DC rush hour.

What good luck, I thought.

Only it wasn't, or so I realized when the replacement lever arrived.

The folks at Suzuki had designed both their clutch and brake levers with a cutout in the metal, right at the point where the lever had snapped. Because people drop bikes all the time. Perhaps you're a new rider, and your balance is uncertain. Or you hit a patch of oil or wet leaves or gravel. Or you're just being a distracted, rushing idiot.

So they'd factored that in, making it much more likely that a low speed drop would still leave you with a ridable motorcycle. It was meant to break manageably, meant to fail in a way that was recoverable.

Which is how you design a system, when you actually care about the people who use it. When you don't want one mistake or moment of misfortune to be catastrophic.

I just wish American society was set up the same way.

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

Our Conflict Algorithm

Simulated Pseudo-Organic Conflict Algorithm from ClearwavePro AJW on Vimeo.

It's a peculiar thing, how the strange new media of the virtual world encourages our darkness.

With my novel coming out in just about a month, I find myself aware that, well, some people just won't like it. They will write reviews that say, eh, this book didn't work for me. Boring, boring, boring, they'll say. And I will cry and be sad. Snif.

And eventually, some troll will get a bee in their bonnet about it, and write things that are nasty, shallow, bitter and deeply unfair.

What is my choice, in such an instance? How am I to respond?

The monkey-mind temptation is to fling myself at them, to summon my rage powers, and to take them down.

Then they respond. Then I respond. Then our friends get into it. The next thing you know, it's a full-on hairball of a dogfight, a churning trackless interweaving of rage-threads and invective.

That means a whole bunch of people spending a whole bunch of time on a website or destination.

Which is exactly what we're supposed to be doing. Fighting is good for business.

And there's something more, something I noticed when a dead-hearted Pharisee wrote an utterly unfair review of a friend's excellent book on Goodreads. This peculiar soul panned a book she hadn't even read, solely because she'd learned it had a couple of bad words in it.

A Christian writes a book about the spiritual process of recovery from a brutal rape that has a smattering of profanity? And the bad words offend another "Christian" more than the rape itself, so much so they feel obligated to write a smug missive about it? Lord have mercy, but some folk have their priorities wrong.

My friend's friends leapt to her defense, calling out the Pharisee. There was the usual back and forth. And when the smoke cleared, what review do you suppose the Goodreads algorithms put right there at the top?

The troll's review, because that was where the energy was. That was, as far as the cold eyes of data were concerned, the most interesting discussion.

Seeing this maddening vortex, I made myself a pledge, in defiance of this dynamic. If I read a terrible, horrible, no good review, I may feel defensive. Scratch that. I will feel defensive.

But I will not let myself manifest that defensiveness. I will not go on the offensive. I will simply allow that some folks have different taste. Or that some trolls are like that, and move on.

Because in this peculiar internet era, the Machine wants us to be fighting, goading us on like a gambler wagering at a drunken barroom brawl, all the while profiting from our anger-addled attention. That's something to keep in mind.

And in defiance of that, put your energies into grace, whenever and wherever you can.

It's a peculiar thing, how the strange new media of the virtual world encourages our darkness.

With my novel coming out in just about a month, I find myself aware that, well, some people just won't like it. They will write reviews that say, eh, this book didn't work for me. Boring, boring, boring, they'll say. And I will cry and be sad. Snif.

And eventually, some troll will get a bee in their bonnet about it, and write things that are nasty, shallow, bitter and deeply unfair.

What is my choice, in such an instance? How am I to respond?

The monkey-mind temptation is to fling myself at them, to summon my rage powers, and to take them down.

Then they respond. Then I respond. Then our friends get into it. The next thing you know, it's a full-on hairball of a dogfight, a churning trackless interweaving of rage-threads and invective.

That means a whole bunch of people spending a whole bunch of time on a website or destination.

Which is exactly what we're supposed to be doing. Fighting is good for business.

And there's something more, something I noticed when a dead-hearted Pharisee wrote an utterly unfair review of a friend's excellent book on Goodreads. This peculiar soul panned a book she hadn't even read, solely because she'd learned it had a couple of bad words in it.

A Christian writes a book about the spiritual process of recovery from a brutal rape that has a smattering of profanity? And the bad words offend another "Christian" more than the rape itself, so much so they feel obligated to write a smug missive about it? Lord have mercy, but some folk have their priorities wrong.

My friend's friends leapt to her defense, calling out the Pharisee. There was the usual back and forth. And when the smoke cleared, what review do you suppose the Goodreads algorithms put right there at the top?

The troll's review, because that was where the energy was. That was, as far as the cold eyes of data were concerned, the most interesting discussion.

Seeing this maddening vortex, I made myself a pledge, in defiance of this dynamic. If I read a terrible, horrible, no good review, I may feel defensive. Scratch that. I will feel defensive.

But I will not let myself manifest that defensiveness. I will not go on the offensive. I will simply allow that some folks have different taste. Or that some trolls are like that, and move on.

Because in this peculiar internet era, the Machine wants us to be fighting, goading us on like a gambler wagering at a drunken barroom brawl, all the while profiting from our anger-addled attention. That's something to keep in mind.

And in defiance of that, put your energies into grace, whenever and wherever you can.

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

Of Jobs and Environmental Accords

I meandered through the car dealership, waiting for the finance folks to process me.

It was new car time, but things were a little slow in the dealership as they tend to be, so I wandered from car to car, sampling them as I waited.

We were getting a Honda, an Accord, because they're just great cars. Reliable. Practical. Efficient. Surprisingly nice to drive.

You can't go wrong with a Honda, or so I've been saying since I convinced my dad to buy his first Honda over thirty years ago. They are fine, fine automobiles. Heck, if I wasn't in the ministry, I could sell 'em.

But what I was reminded of as I wandered through the dealership was a little peculiarity of Honda in America: most Hondas are American cars. Checking the manufacturer labels on the sides of those minivans and sedans and small utes, you can find the place of manufacture and the parts content.

Most of the vehicles on that dealership floor were made in America, produced by American workers in Honda factories in Ohio. Or in Kentucky. Or in Tennessee. Seventy percent or more of the parts content? American.

In an age where Jeeps are made in Europe, and Dodges in Canada, and Fords in Mexico? I'd say Honda counts as American.

But not our Accord, unfortunately. I was disappointed to discover it, because while I don't care a whit about which CEO of which global corporation pockets a percentage of my purchase, I like supporting American factory workers.

We'd gotten the hybrid version, because DC traffic is just so heinous. And I like the often silent running of a hybrid, and the lower impact on the environment. That, and we got a great deal, because with gas so cheap, hybrids are languishing. It cost us less than the price of the average vehicle in America.

Alone among the Accords you can buy in America, the hybrid was built in Saitama, Japan. It used to be made in America, back as recently as 2015. But American suppliers haven't invested in battery production and electric motor production in the same way as the Japanese, and Honda couldn't get the parts it needed to manufacture the last version here. Shortages gummed up their production lines.

So for the new iteration of the Accord, those jobs left these shores. America fell a little further behind, and our lack of attention to the future meant fewer Americans working.

And sure, we're talking Honda Accords and not a Paris Accords.

But the pungent symbolism did not escape me.

Thursday, June 15, 2017

Divine Sovereignty and the Multiverse

The concept of predestination exists for a reason. As a doctrine, as a theological construct, and as a way of understanding creation, it exists for the sole purpose of affirming divine sovereignty.

God, the Alpha and the Omega, the Creator of the Universe, the Almighty and Eternal? God is in charge. Nothing happens, but that the I Am That I Am wills it. From the start of time and space to its conclusion, every last little thing that happens is under the authority of the One that makes Heaven and Earth.

If this is not true, then God is not God, and God is not worthy of worship.

That's pretty much the classically orthodox Christian position, as laid out by Brother Augustine and John Calvin, Esquire.

I am completely down with that, with a rather notable exception.

I don't think it means precisely what Calvin and Augustine thought it meant, because I don't understand creation in the same way. I live in neither the year 420 nor the year 1550, and have the advantage of centuries of human knowledge.

Along with many cosmologists and a surprisingly large number of physicists, I view creation as multiversal. There is not one time and space, but rather all times and spaces. Everything that can exists does exist, and what we experience in the vastness of our time and space is just an infinitesimal slice of being.

Along with many cosmologists and a surprisingly large number of physicists, I view creation as multiversal. There is not one time and space, but rather all times and spaces. Everything that can exists does exist, and what we experience in the vastness of our time and space is just an infinitesimal slice of being.

I believe this for a range of reasons, some of which lie in mystic experiences that make me sound a bit crazy. But those encounters resonate with what science seems to be discovering, which is why I don't just write them off as me being a little wackadoodle.

More importantly, my understanding of creation as multiversal is the only way...as I see it...to integrate the statement that God is Sovereign with the statement that God is Love.

Classical predestination...meaning, God is the Author of the single linear timeline that we together are experiencing...has two primary theological flaws.

First, it asserts that this is the best of all possible universes. Calvinists will argue this with a straight face, trying to assert that the bloody mess of human history is just God being a little coy about God's goodness. "Really, it'll be the best! The very best," says the classical Calvinist YHWH. "I'll tell you the reason for all of this chaos and horror soon. Very soon, and it'll be good. So good! And you'll be amazed. Believe me."

We get enough of that kind of [bovine excrement] from the fools we have chosen to lead us.

I don't believe that for a moment, because believing that impinges on God's sovereign power. Asserting that God is only capable of creating a single nonvariant thing imprisons God's will within our time and space. But my God, to sound a bit like a praise song, is a mighty God. My God can do more than that. My God can do everything that can possibly be done.

Sure, you can argue that God is limited, that God must do only one thing because that one thing is God's will. But then your god with a small "g" is smaller than mine. Weaker. Not actually omnipotent at all, unless you define down omnipotence to less than we can imagine.

The second flaw with classical predestination is that it eliminates moral agency. If there is just one way everything can happen, and the Creator of the Universe has absolute control down to the subatomic level, then we are not empowered to make any meaningful choices. Everything that is done is done because God is doing it. Period.

And if that is so, then we choose nothing. And if we do not have the power to choose, then we are not culpable for our actions. If you have only one option, then you have no options. We become objects, meat machines whose Free Will is simply an illusion, a mirage cast by the shimmering heat of Divine Authority.

As a cosmology, I suppose I could see where that might have some purchase. The problem with that?

Jesus.

I mean, not "Jesus" as an appropriately blasphemous epithet cast at a monstrous, soulless clockwork, but "Jesus" as the one who manifests and embodies God's Love.

At the heart of the Gospel lies the assumption that change is possible. "Repent, for the Kingdom of God is at hand," says the Nazarene. To authentically repent, one must have the power to choose, to select one path rather than another.

Without that capacity for choice...real and fraught with mortal peril...we are not moral creatures. Neither would we be made in the image of God, or at least, not any god worth turning to in hope. We, like the "god" of a single mechanistic way of being, would be functionally helpless, trapped, unable to create, unable to shape reality.

For God to be God, the divine power to create must infinitely transcend the creation we perceive.

And for God to be love, we must be free to choose...really, truly choose...to love God back.

Which is why, quite frankly, a multiverse is necessary, if the sovereignty of the God we Jesus-folk know in Christ is to be preserved.

I don't believe that for a moment, because believing that impinges on God's sovereign power. Asserting that God is only capable of creating a single nonvariant thing imprisons God's will within our time and space. But my God, to sound a bit like a praise song, is a mighty God. My God can do more than that. My God can do everything that can possibly be done.

Sure, you can argue that God is limited, that God must do only one thing because that one thing is God's will. But then your god with a small "g" is smaller than mine. Weaker. Not actually omnipotent at all, unless you define down omnipotence to less than we can imagine.

The second flaw with classical predestination is that it eliminates moral agency. If there is just one way everything can happen, and the Creator of the Universe has absolute control down to the subatomic level, then we are not empowered to make any meaningful choices. Everything that is done is done because God is doing it. Period.

And if that is so, then we choose nothing. And if we do not have the power to choose, then we are not culpable for our actions. If you have only one option, then you have no options. We become objects, meat machines whose Free Will is simply an illusion, a mirage cast by the shimmering heat of Divine Authority.

As a cosmology, I suppose I could see where that might have some purchase. The problem with that?

Jesus.

I mean, not "Jesus" as an appropriately blasphemous epithet cast at a monstrous, soulless clockwork, but "Jesus" as the one who manifests and embodies God's Love.

At the heart of the Gospel lies the assumption that change is possible. "Repent, for the Kingdom of God is at hand," says the Nazarene. To authentically repent, one must have the power to choose, to select one path rather than another.

Without that capacity for choice...real and fraught with mortal peril...we are not moral creatures. Neither would we be made in the image of God, or at least, not any god worth turning to in hope. We, like the "god" of a single mechanistic way of being, would be functionally helpless, trapped, unable to create, unable to shape reality.

For God to be God, the divine power to create must infinitely transcend the creation we perceive.

And for God to be love, we must be free to choose...really, truly choose...to love God back.

Which is why, quite frankly, a multiverse is necessary, if the sovereignty of the God we Jesus-folk know in Christ is to be preserved.

Saturday, June 10, 2017

Hygge Christianity

I encountered the word in an article, and had no idea what it meant. "Hygge." Hygge? I had no idea what that word was. A noun? A verb? An adjective? All of the above? I didn't even know how to say it. Higgie? High-guh-geh?

This was an offense to my vocabulary, which is a source of some hopefully-less-than-mortal-pride, so I looked it up.

"Hoo guh," it's pronounced, and it's Danish, a term that is an integral part of that culture's self understanding. Apparently, the word hygge has been floating around for half a year as the latest next big thing, buzzing about in the fad-hungry networks of cosmopolitan souls who are considerably more hip than I.

It means, or so I learned from the New Yorker article on the subject (but of course, the New Yorker), a "quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being."

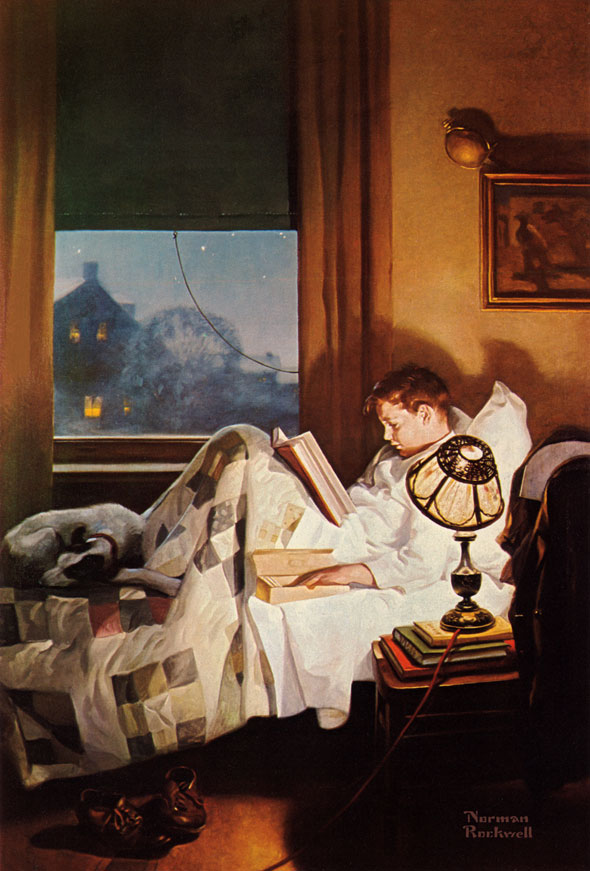

Hygge speaks to a particularly Scandinavian view of existence, of having enough but not too much, of enjoying simple comforts and the pleasurable company of others. It's a warm flannel sheets kind of word, a sitting tending the fire kind of word. It's very hobbitish, very Norman Rockwell, very Narnian.

And I wondered, as I thought, to what degree that concept translates to the life of Christian faith.

Not well, generally.

Jesus folk seem to have trouble with it. We're good at stern Pharisaism, that bright bitter granular pursuit of our neighbor's sins. Hygge makes the Jesus Pharisee think of John the Revelator's contemptuous letter to Laodicea, a place of warm tepid water that has no place in a world that deserves to burn in the hell-fires of our...oops, we mean, God's...ever-righteous wrath.

We're good at devouring anxieties, fretting about every last thing that might be wrong with the world. How can you indulge in hygge, when everything is terrible and we must be continually outraged about the latest thing some fool said on twitter? Hygge, one might sniff, is just bourgeois and privileged, and an impediment to our mission to afflict the world whenever it wants to just not stress out for half a moment.

And we're particularly good, we American Christians, at the big bright sparkle of AmeriChrist, Inc., in giant arenas with Jumbotrons and multi-level parking garages. We prefer our faith commodified to an industrial era shine, not small and quiet and uninterested in a 55 million dollar campaign to build a new state of the art worship complex.

Which is the farthest thing from cozy, and the farthest thing from "just enough."

This is a pity, because if you can't do hygge, you can't really offer comfort to those who suffer and hunger for a place of sanctuary. If you can't do hygge, you can't show hospitality to neighbor and stranger alike.

And an absence of hygge means an absence of grace, without which this whole Jesus endeavor seems rather pointless.

This was an offense to my vocabulary, which is a source of some hopefully-less-than-mortal-pride, so I looked it up.

"Hoo guh," it's pronounced, and it's Danish, a term that is an integral part of that culture's self understanding. Apparently, the word hygge has been floating around for half a year as the latest next big thing, buzzing about in the fad-hungry networks of cosmopolitan souls who are considerably more hip than I.

It means, or so I learned from the New Yorker article on the subject (but of course, the New Yorker), a "quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being."

Hygge speaks to a particularly Scandinavian view of existence, of having enough but not too much, of enjoying simple comforts and the pleasurable company of others. It's a warm flannel sheets kind of word, a sitting tending the fire kind of word. It's very hobbitish, very Norman Rockwell, very Narnian.

And I wondered, as I thought, to what degree that concept translates to the life of Christian faith.

Not well, generally.

Jesus folk seem to have trouble with it. We're good at stern Pharisaism, that bright bitter granular pursuit of our neighbor's sins. Hygge makes the Jesus Pharisee think of John the Revelator's contemptuous letter to Laodicea, a place of warm tepid water that has no place in a world that deserves to burn in the hell-fires of our...oops, we mean, God's...ever-righteous wrath.

We're good at devouring anxieties, fretting about every last thing that might be wrong with the world. How can you indulge in hygge, when everything is terrible and we must be continually outraged about the latest thing some fool said on twitter? Hygge, one might sniff, is just bourgeois and privileged, and an impediment to our mission to afflict the world whenever it wants to just not stress out for half a moment.

And we're particularly good, we American Christians, at the big bright sparkle of AmeriChrist, Inc., in giant arenas with Jumbotrons and multi-level parking garages. We prefer our faith commodified to an industrial era shine, not small and quiet and uninterested in a 55 million dollar campaign to build a new state of the art worship complex.

Which is the farthest thing from cozy, and the farthest thing from "just enough."

This is a pity, because if you can't do hygge, you can't really offer comfort to those who suffer and hunger for a place of sanctuary. If you can't do hygge, you can't show hospitality to neighbor and stranger alike.

And an absence of hygge means an absence of grace, without which this whole Jesus endeavor seems rather pointless.

Saturday, June 3, 2017

When the Bible Is Profane

It's not been the easiest class.

Our goal: a full, engaged reading of the Book of Judges.

I'd committed to leading it a couple of months back, being the Teaching Elder at my little congregation and all, and I don't regret it.

It's a fascinating book, truly and genuinely ancient, chock full of tales that rise out of the late Bronze Age. Here, songs and stories that are over three millennia old, narratives that rise up from deep in the primal memory of the people of Israel.

That alone makes them worthy of study, and worthy of deeper exploration.

But it doesn't make them any less brutal. Judges starts with a captive king having his toes and thumbs cut off, and it pretty much goes downhill from there. It's chock full of the ultraviolence, as the imprisoned Alex DeLarge discovered to his delight, as much so as any of the savage tales of our violence-loving culture. The heroes of the tale nail sleeping men's heads to the ground with spikes, and flay village elders to death with thorned branches. They butcher their own children. Even Samson, Samson of countless Sunday school coloring books? He's driven by lust, betrays his sacred oaths, and murders entire villages to pay off his debts.

It ends with mass abductions and rapes, as a tribe of Israel storms into a local festival to kidnap young women with the sole intent of using them as chattel breeding slaves. It's something straight out of the Boko Haram playbook.

Next to the book of Judges, Deadpool and Judge Dredd seem like callow newbies.

And yet. Were I fool enough to read any of this in worship, I'd have end my reading with "This is the Word of God," to which the good souls of my little church would have to stammer out, "Thanks...be to...cough...God?"

There is, quite frankly, nothing sacred about it.

Fundamentalism, in its reflexive idolatry, assumes that there axiomatically must be. But there is not. Judges is unrelentingly profane, a story of blood and betrayal and human horror. It is so by design.

That does not mean that it is unworthy of inclusion in our sacred story.

All Scripture is God-breathed, and useful for teaching, as that 2 Timothy touchstone goes, and the book of Judges is no exception.

It is worth teaching because it reminds us of how easily human power corrupts, and how far back our love of blood goes. It is worth remembering because it holds us to account, and reminds us that our understanding of God's intent for us sometimes wanders far from grace, compassion, and justice.

And is it God's Word? Sure, because nothing in creation is not God's self-expression.

Even those wildly profane things that have nothing to do with God's grace, if we have the wisdom to learn from them.

Our goal: a full, engaged reading of the Book of Judges.

I'd committed to leading it a couple of months back, being the Teaching Elder at my little congregation and all, and I don't regret it.

It's a fascinating book, truly and genuinely ancient, chock full of tales that rise out of the late Bronze Age. Here, songs and stories that are over three millennia old, narratives that rise up from deep in the primal memory of the people of Israel.

That alone makes them worthy of study, and worthy of deeper exploration.

But it doesn't make them any less brutal. Judges starts with a captive king having his toes and thumbs cut off, and it pretty much goes downhill from there. It's chock full of the ultraviolence, as the imprisoned Alex DeLarge discovered to his delight, as much so as any of the savage tales of our violence-loving culture. The heroes of the tale nail sleeping men's heads to the ground with spikes, and flay village elders to death with thorned branches. They butcher their own children. Even Samson, Samson of countless Sunday school coloring books? He's driven by lust, betrays his sacred oaths, and murders entire villages to pay off his debts.

It ends with mass abductions and rapes, as a tribe of Israel storms into a local festival to kidnap young women with the sole intent of using them as chattel breeding slaves. It's something straight out of the Boko Haram playbook.

Next to the book of Judges, Deadpool and Judge Dredd seem like callow newbies.

And yet. Were I fool enough to read any of this in worship, I'd have end my reading with "This is the Word of God," to which the good souls of my little church would have to stammer out, "Thanks...be to...cough...God?"

There is, quite frankly, nothing sacred about it.

Fundamentalism, in its reflexive idolatry, assumes that there axiomatically must be. But there is not. Judges is unrelentingly profane, a story of blood and betrayal and human horror. It is so by design.

That does not mean that it is unworthy of inclusion in our sacred story.

All Scripture is God-breathed, and useful for teaching, as that 2 Timothy touchstone goes, and the book of Judges is no exception.

It is worth teaching because it reminds us of how easily human power corrupts, and how far back our love of blood goes. It is worth remembering because it holds us to account, and reminds us that our understanding of God's intent for us sometimes wanders far from grace, compassion, and justice.

And is it God's Word? Sure, because nothing in creation is not God's self-expression.

Even those wildly profane things that have nothing to do with God's grace, if we have the wisdom to learn from them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)