"So, how are you doing," I asked, as Mom and I drove to have dinner with my son and daughter-in-law. It can be a little hard to tell with Mom, who tends to view everything as positively as possible, who'll answer the phone cheerily almost under any circumstance, who sees the good in nearly everything, in an Eric Idle Bright-Side-of-Life sort of way.

"You know the Aztecs? How they'd cut out someone's still beating heart? I'm doing like that," she replied, matter of factly, while still humming and bopping along to the classic 50's playlist I'd spooled up for our ride.

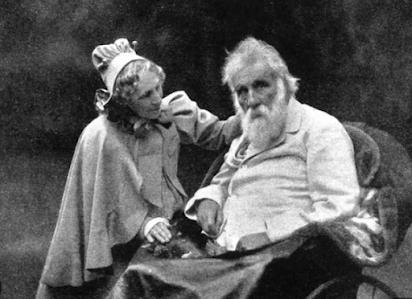

After fifty five years with Dad, and after being with him all the way through the hourglass-trickle of congestive heart failure, of course that's how she feels. He was so present. Every few minutes, Dad calling her to get him something, or to come see a thing, or to come hear a thing. Dad, the extrovert, with Mom his only audience. Dad, who doted on her, who told her he loved her every single day. Dad, who would flirt with her some evenings when I was taking a care shift, embers of a playful eroticism between them still glowing in his fading flesh, the sort of banter that would have mortally embarrassed me as a fifteen year old. He was still that young man in there, and still...as he would say over and over...smitten with her. "I remember," he would say, as I helped him get ready for bed, "that time she took my arm, and she looked up at me, and Oh that look she gave me! Oh, she got me." He never stopped being smitten with her, and never stopped telling her so.

Of course Mom feels the emptiness, and grieves way down deep. Doing things, she says, is hard. She just doesn't feel like doing much of anything, which is why I'm trying as best I can to manage all of the things that must happen following Dad's death.

I still wonder at my own grief. Over the last few days, it's shifted. It's more of a heaviness now, and doing things has become harder. It's harder to concentrate myself, to focus energies. Motivation is difficult, and requires much more intention. Get up. Go do that thing. C'mon. Do it. I manage to get it done, but everything feels like a bit more effort. "A mild situational depression," I'd say. It's not overwhelming. I know what heavier, deeper depression feels like. This isn't that. It isn't that peculiar energy, that anxious paralysis, that fatigue that traps you in a paradoxically restless inertia, a shimmering listlessness.

I'm still showering. Still changing clothes. I'm still able to tend to the house.

I can still write. I can still work. How am I doing? I am still "doing."

Rache and I talked about that last night, about work and grieving and doing. "We should be able to take time away when we're grieving," she said. "Not just a few days, but weeks. Why shouldn't we be able to do that?"

It's a valid thing, and a cultural failing. But my work differs a smidge from much of the labor most do in the world. Pastoring a small church is a different animal, unlike not only secular work, but also unlike work in a larger church. There are fewer organizational requirements. It's complex, sure, but it's organic complexity rather than institutional complexity. To effectively pastor a small church, that community can't be simply your job. It must become your community. It's your place of strength and support, where you're not the "boss" or "above," but right there in it. You aren't your role. You're you.

Small church is not the place you go to be the font of all wisdom, a place of ego. It must be the place where you are fed, where you feel supported, where you hear the voices of brothers and sisters who labor alongside you. Not beneath you, or subordinate to you, but with you.

Yesterday when I arrived at church a couple of members were already there, because our bustling Little Free Pantry was about to receive a delivery, a large contribution of food from the lovely souls at a local Buddhist temple. Eight hundred pounds of it, delivered by monks and laity, and it all needed to be moved from the backs of their 'utes into our storage area.

Had it been an afternoon meeting, a committee to plan a commission to form a task force to review policies, procedures, and protocols, I might have struggled. Focus and energy might have been hard to find.

But I was doing, and the doing was easy.

What I found myself doing was carrying thirty pound bags of carrots and onions and taters, boxes of cans, crates of jars, alongside Presbyterian elders and earnest Buddhists, helping set a table for those who might not otherwise know where their next meal is coming from. It was real, and I felt that reality in my arms, in my back.

It felt good, to be doing that.