Which is why an article in yesterday's Washington Post struck me. Though young folks might be struggling, what they aren't particularly interested in are Federal government jobs. There are a range of reasons for this.

Among them are the culturally reinforced sense that the gummint ain't to be trusted, that it's ineffectual, that it's a sprawling, soul-crushing bureaucratic nightmare, an endless morass of silos and turf wars and dizzying, Byzantine requirements.

This isn't entirely true, but neither is it entirely untrue. Layered on top of that comes the financial uncertainty of an institution in decline, as positions fall and fade away, with those who remain clinging doggedly to their jobs.

Layered on top of this, in order to enter this Fun Land of Big Joy and Happiness in the first place you have to negotiate a hire process that is so opaque, clumsy and slow as to render it almost inert.

I have often noted that while contemporary nondenominational Christianity has embraced the values of the marketplace, we old-liners still mostly emulate the structures and dynamics of government.

So when it comes to bringing new voices into the mix, it occurs to me that we have precisely the same problems as government, for the same reasons. Having been through the Presbyterian process, I can say without question that it is not the sort of thing that resonates with the kids these days. They're just not hip to it. It's not groovy, man. It's, like, totally gnarly, dude. OMG.

Which is why, though I'm forty-five years old and there's white in my beard, I look around at meetings and note that I'm still one of the "young ones."

This is not a good sign.

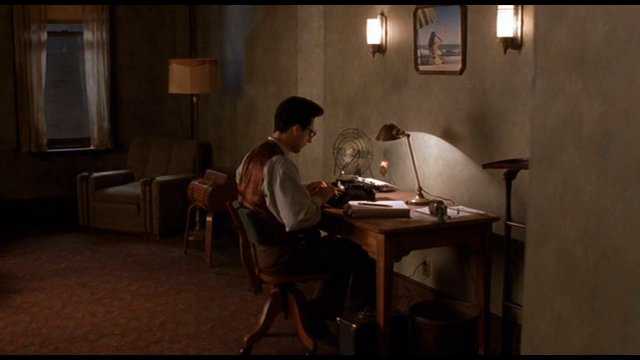

Oh, I was young when I started. I was twenty eight, which didn't feel young at the time. By the time I was done, I was halfway through my thirties. Having committed myself to avoiding the call-sucking siren song of debt-financed education, it took me seven years to negotiate the process. Those years were good, and many of the relationships and conversations I had with those charged with walking me through that process were positive, both testing and affirming my call.

But those years were also layered with duplicative toils, sudden snares, and dangerous oversights. A few examples:

Toils: On the one hand, we Presbyterians are obligated to have a seminary degree, with tests and exams and the like, administered by professors at accredited institutions. On the other, we're required to take Ordination exams that mirror the contents of that education. I never understood the logic of this. If I've successfully completed biblical coursework from an accredited institution, why take yet another exam? I know the counterarguments: that seminaries are inadequate, that Ords provide uniformity. But then why require seminary, if we're so convinced it is inadequate? And why pretend that the Ords--graded by laity and pastors--are more "uniform?" They are, in my experience, just as subjective.

Snares: Five years in, my committee--whose membership had rotated several times--suddenly informed me that I needed to get forty hours of clinical pastoral education. Was it required by the denomination? No. Was it a presbytery requirement? No. Had it been discussed, ever, up until that point? No. Was I pursuing a call to be a hospital, military, or hospice chaplain? No. I was working, and in seminary, and had two young children, and was interning in a congregation. I could see no clear connection between this requirement and the realities of congregational leadership, so I demurred. If this was to be a requirement, I could not fulfill it. Had the issue been pressed, I would have removed myself from the process. It was not, thank the Maker. This happens often, not out of malice, but from the clinical remove a committee often has from the reality of those they are shepherding and testing.

Dangers: In the seven years it took me to negotiate the call process, I was never required to show my capacity as a preacher or a spiritual leader of people. I never preached. I never demonstrated that I could teach or lead a gathering. Not once. There were a lot of papers and essays and forms and meetings. But not nearly enough of it directly spoke to the skills required to preach and teach the Gospel and energize a community. This is dangerous, because it sets up an expectation on the part of a candidate that they've got the skill set that resonates with a congregation...when in fact, they have not.

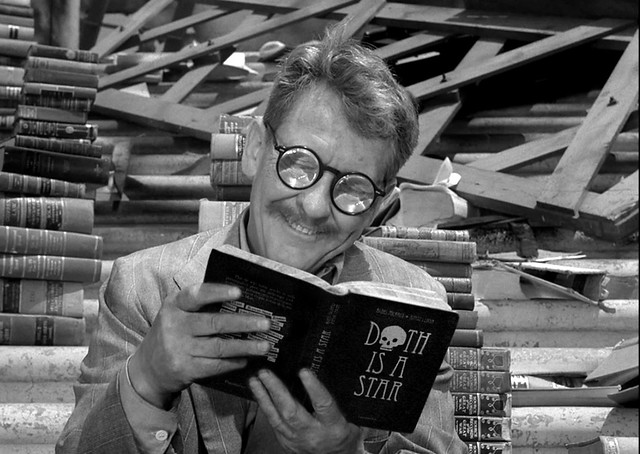

More dangerous still, our processes bear little resemblance to the shattering, transformative experience of call itself. You know, call? When God shows up in your life and demands it? That's the stuff of dreams and visions, of the fire that gnaws at your bones. If we confuse test taking and process management skills with call, we set up a dangerously inaccurate misunderstanding, both for our churches and for those testing their call.

Years of requirements, many of which have no meaningful connection to the spiritual and material demands of our vocation. Thickets of uncertainty. A debt financed education. And ultimately? Once you've gotten through that?

It begins again, with the wildly clumsy and uncertain process of seeking a call.

And we wonder why younger folks steer away.