Her voice was agitated, and she needed prayers right away for her grandson. "What's going on?" I asked.

"Well, he's in prison in Mexico," she began, "and he called me because he needed bail money to..."

My anticipated prayers and advice took a different turn, mostly that she might get to Wells Fargo in time to stop the wire transfer she'd just authorized.

I had a long, long talk with my Dad about that last one, after I'd spent an hour rooting out the malware the "Microsoft Help Desk" person had installed on my parents desktop.

Where once being old meant that you had a familiarity with the world, the relentless pace of churn and change in our culture simply means that your lifetime of developed experience no longer has any purchase. Even in cultures where the elderly were more honored and revered than in our own adolescence-focused society, they were still in a position to be taken advantage of.

The ancient stories of scripture offer up multiple witnesses of age and its weaknesses, of how easily those who seek advantage can take it from the unwary and unprotected old.

Take, from Torah, the way that Eli's corrupt sons took advantage of their heritage, stealing his honor and using their inherited priestly position to help themselves to offerings and women, so shaming him that he took a life-ending fall.

Or again and more sharply in Torah, Jacob's brazen scamming of blind Isaac, Jacob the sly mama's boy, a trickster-archetype, approaching his visually impaired father with masked voice and disguised form, stealing a blessing and a birthright that was not his.

Or Nathan and Bathsheba in 1 Kings 1, working together to gaslight the addled, unwarmable David into supporting Bathesheba's child Solomon over Haggith's son Adonijah.

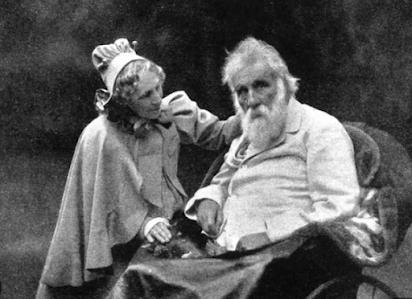

The weakness of the old makes them easy prey for those who want to take wealth or power for themselves. It makes them just as easy to ignore, or to warehouse, or to treat as something less than a person.

If we view power and strength as the measure of a person's worth, then we are just as prone to diminishing those who are no longer what they once were. We begin to treat the elderly in the same way that the ancient world treated children...like they are not fully human and worthy of treating with decency.

That view of those who are less than fully able is anathema to an authentic Christian faith. Weakness and vulnerability are not to be mocked, belittled, or viewed as an opening for advantage. Those who find themselves without power are precisely the souls that the Crucified One demands that we protect and care for, not in spite of their weakness but because of it.

Because for all the different ways we delude ourselves into believing we will never age, that we ourselves will never be weak or vulnerable? That's as false as Donald Trump's hair. We will all of us eventually be that person, unable to stand on our own, fuddled and lost and a little confused. How we...as persons, and as a culture...treat those who cannot fend for themselves is the measure by which we will be judged.