My recent reading of Adolph Hitler's Mein Kampf was difficult, for a range of reasons.

The first of those was, unsurprisingly, his complete and utter hatred of the Jews. Knowing what came of that, for any not-evil human being, that's hard enough to read.

But as a Presbyterian pastor with a Jewish wife and children, it made wading through this monstrous book particularly difficult. Here, a man who would given half a chance have murdered my children, and killed my family. Five hundred and twelve times in that godforsaken book, he spits out his hate, hate on almost every page, a hatred for everything Jewish that is deeply, pervasively demonic.

And here I was, spending time in his mind, and engaging with his thoughts, hundreds and hundreds of pages of them. I felt like Socrates, half-empty cup in hand. My soul recognized the bitter evil of it, tasted that it is toxic. But still, on I drank, forcing myself to take it down, to know it more intimately.

As a person of faith, I tasted in his writing something of the faith that motivated Adolph Hitler. And he did talk a great deal about faith.

Judaism, as far as Hitler was concerned, was not a faith. His hatred of the Jews was not because it was a different religion. As far as he is concerned, it was not a faith at all. He dismisses that as a lie told by liberals, a secret back door to allowing Jews to be just one belief system among many in a pluralistic culture, rather than the source of all evil that Hitler endlessly, relentlessly claimed. Jews, Hitler argues in Mein Kampf, are only a nation and a race, bound together not by a legitimate covenant with God, but by blood and ethnic identity. Given how oddly this sounds against ongoing conversations within Judaism itself about what constitutes Jewish identity, it was peculiar to hear what Judaism's greatest enemy had to say.

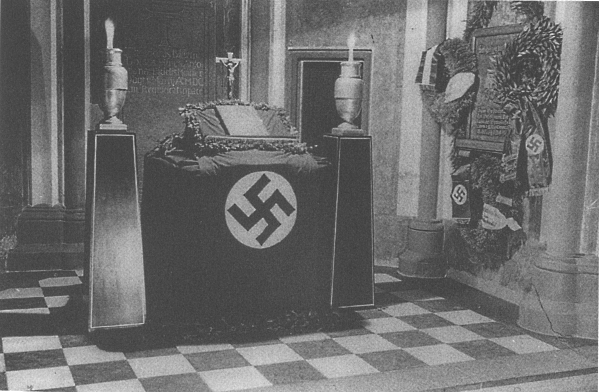

Just as hard for me, as a follower of Jesus of Nazareth, was the way that Adolph Hitler coopted the language of Christianity into his service. He uses Christian language and symbol as a way to cement his political power.

On multiple occasions, Mein Kampf coopts the New Testament, using images and snippets from the parables and storytelling of Jesus to make a point.

"Like a camel through the eye of a needle," Hitler says. "No man can serve two masters," Hitler says. I wince at the references, familiar from the voice of my own Master. And of course, he uses the "cleansing of the Temple" image, the go-to Jesus-story for people who want justification for their hatred and desire for violence.

But the references are warped. For example, Hitler was using the camel/needle story in Mein Kampf not to challenge wealth and power as Jesus did, but to attack the idea that representative democracy can ever produce strong leadership. The cleansing of the temple? For Hitler, it's about how Jesus--the Jew, who taught other Jews like a rabbi and used the Torah and the prophets as his foundation--wanted to purge the world of all things Jewish. Hitler's misusage was insane. It had nothing at all to do with the Gospel or Jesus of Nazareth.

Because Adolph Hitler's faith was in martial power, national pride, and cultural purity. That was his god, the object of his worship, the teleological yearning of his mad, misbegotten Reich. The shallow cultural Christianity of the German people was just a means to that ultimate end.

But tapping that source of power worked, clearly, in a potent way. What it did was take the in-group language of Christian faith, and said: look, I know how to speak this way. Look at how I am just like you, about how I share what you share.

He stripped the words away from the reality towards which they were intended to point. No longer do they declare a Kingdom of grace, where the outcasts are welcomed, and the broken are made whole. Hitler uses them and warps them to point to another reality, a darker one, seething with nationalist resentment, racial pride, and violence, the antithesis of the Gospel.

Some Christians realized this demonic influence, and fought it. They were few in number, and died for their resistance. My own Presbyterian denomination remembers their witness, recorded in the Barmen Declaration, as part of our Constitution. It stands as reminder of the terrible danger of allowing our faith to be coopted by political power. Never again, we say, and we keep that memory close and precious.

My reading of the most potently evil book of the twentieth century reminded me of how careful we need to be, as power seeks to take, corrupt, and use the language of our faith to control us.

And right now, we need to be very, very careful.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Blog Archive

-

▼

2015

(129)

-

▼

September

(15)

- The Enemies of the Constitution

- Pope Francis and Qualitative Leadership

- The Rise of Sharia Law in America

- Faith, Privilege, and Power

- Impermanence Imbued with Presence

- If It All Came Out Even

- The Shamans of Mammon

- When Power Coopts Our Faith

- Seven Ways You Can Be Like Hitler

- Narrative, Ambiguity, and Apocalypse

- What Fighting for Your Religious Freedom Looks Like

- The Gatekeeper

- The Wall Around Power

- My Rights and Your Rights

- My Inclusive Language Heresy

-

▼

September

(15)